Since the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Alice v. CLS Bank, patent stakeholders have faced many difficulties navigating the world of patent-eligibility. Through many Federal Circuit decisions and Guidance given by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) since Alice, there is some, but not complete, clarity on what is patent-eligible subject matter, especially for the financial services industry and any industry where software or computing forms a core part of its technology (e.g., diagnostics, analytics, data transmission, cloud-based computing, etc.).

Many are still calling for further clarity on the patent eligibility of software claims and are still questioning the ability to obtain software-based patents in multiple industries. But, there are some steps that a patent applicant or owner can take to place their cases in the best posture for overcoming a §101 challenge.

Background

On June 19, 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its decision in Alice Corp. Pty Ltd. v. CLS Bank International, holding that computerized abstract patent ideas are not patent eligible. Specifically, the Supreme Court determined that the claims at issue “simply instruct[ed] the practitioner to implement the abstract idea of intermediated settlement on a generic computer,” and were thus abstract. Subsequently, the Federal Circuit has issued several pro-eligibility decisions. However, while these pro-eligibility decisions have provided positive data points for pro-patent-eligible claims, they are far outnumbered by decisions holding claims ineligible, and thus there continues to be uncertainty among stakeholders.

USPTO Guidelines

The USPTO has issued various guidelines on subject matter eligibility in an effort to bring some consistency to examination of computer-implemented innovation. The first set, issued March 4, 2014, was a response to the Supreme Court’s decisions in Mayo v. Prometheus and Myriad. This guidance was specific to claims involving laws of nature/natural principles, natural phenomena and/or natural products. On June 25th, 2014, the day after the Supreme Court’s decision in Alice, the USPTO issued guidance specific to claims involving abstract ideas. Further guidance was issued on April 19, 2018 (the Berkheimer memo). The most recent guidance was issued on January 7, 2019, with a clarifying update issuing on October 17, 2019.

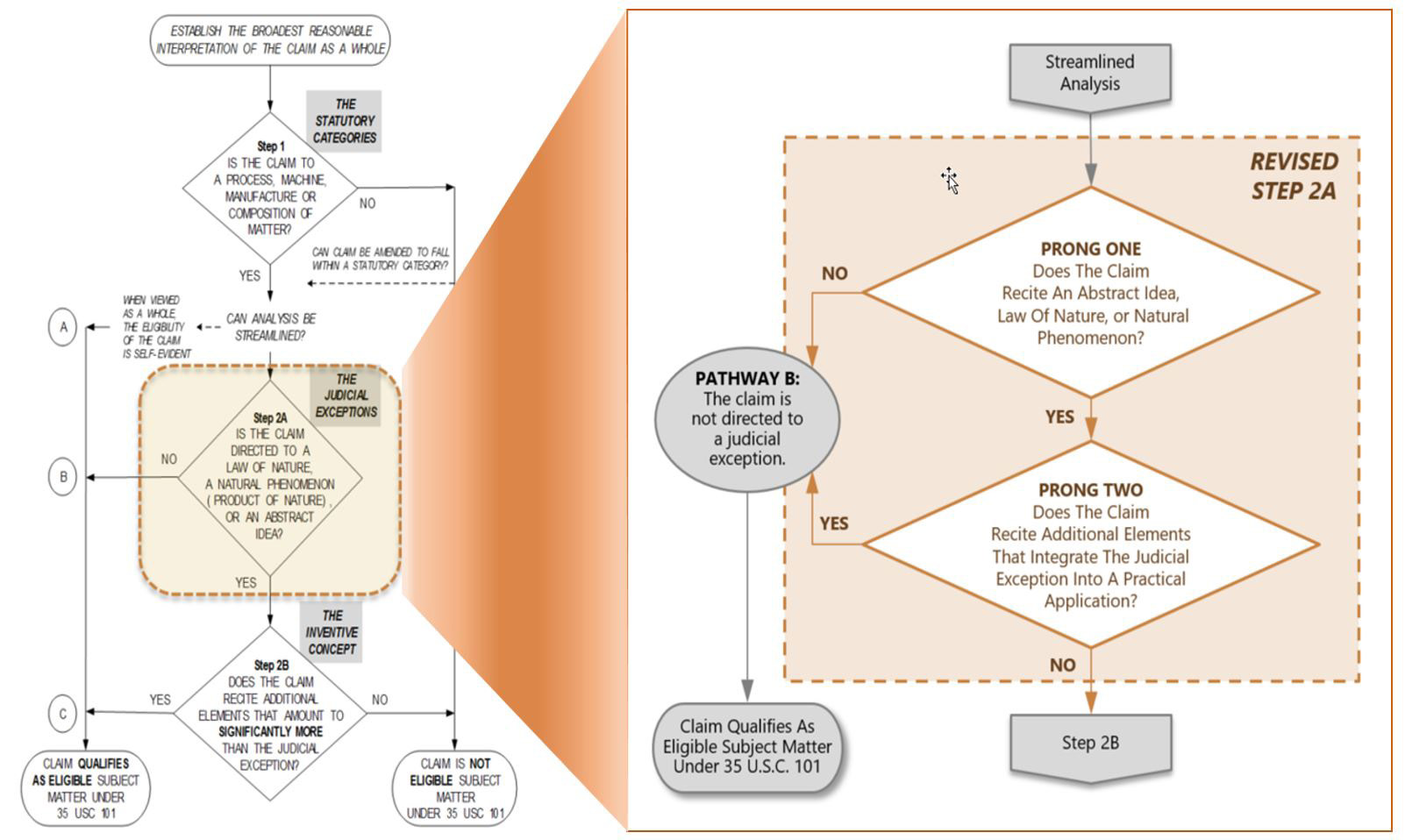

In general, the 2019 revised patent subject matter eligibility guidance revamped the procedures for determining patent eligibility in the following key ways:

- The first step of the Alice/Mayo test was revised—providing three categories of subject matter that are considered abstract ideas: mathematical concepts, certain methods of organizing human activity, and mental processes. Only concepts that fall into those groupings can be rejected as “abstract ideas.”

- Even if a claim recites an abstract idea, the claim is not “directed to” the abstract idea if the idea is integrated into a practical application.

- A claim that recites an abstract idea, but is not integrated into a practical application, is considered “directed to” the abstract idea under Step 2A and must then be evaluated under Step 2B (inventive concept) to determine the subject matter eligibility of the claim.

Combined, the UPSTO’s guidance set out the following required process for any claim directed to a judicial exception:

Subject Matter Eligibility Test for Products and Processes

The combined guidance further:

- Provides examples of both statutory (patent-eligible) and non-statutory (not patent-eligible) claims, along with accompanying analysis.

- Includes a requirement that Examiners address each and every claim element, and each individual claim. Specifically, the guidance notes that “claims do not automatically rise or fall with similar claims in an application.”

- Paves a smoother path toward patenting computer-implemented innovation. Examiners must (1) Identify the specific limitation(s) in the claim under examination (individually or in combination) that the examiner believes recites an abstract idea and (2) Determine whether the claimed subject matter falls into one of the enumerated categories:

- Mathematical concepts — mathematical relationships, mathematical formulas or equations, mathematical calculations;

- Certain methods of organizing human activity — fundamental economic principles or practices (including hedging, insurance, mitigating risk); commercial or legal interactions (including agreements in the form of contracts; legal obligations; advertising, marketing or sales activities or behaviors; business relations); managing personal behavior or relationships or interactions between people (including social activities, teaching, and following rules or instructions); and

- Mental processes — concepts performed in the human mind (including an observation, evaluation, judgment, opinion).

- Claims that do not recite matter that falls within one of these groupings should pass the eligibility test, and the analysis should end, except in very rare circumstances.

The 2019 Guidance further provides the following guidance for Examiners and Practitioners:

- When an examiner identifies an abstract idea and proceeds to Prong 2, they must evaluate whether the claim integrates the abstract idea into a practical application.

- Examiners should evaluate integration into a practical application by:

- Identifying whether there are any additional elements recited in the claim beyond the judicial exception(s); and

- Evaluating those additional elements individually and in combination to determine whether they integrate the exception into a practical application.

- Claims integrate the abstract idea into a practical application when:

- An additional element reflects an improvement in the functioning of a computer, or an improvement to another technology or technical field;

- An additional element implements the abstract idea with a particular machine or manufacture that is integral to the claim;

- An additional element effects a transformation or reduction of a particular article to a different state or thing; and

- An additional element applies or uses the abstract idea in some other meaningful way beyond generally linking the use of the abstract idea to a particular technological environment, such that the claim as a whole is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the exception.

- Claims do not integrate an abstract idea into a practical application if:

- The additional elements merely recite the words “apply it” (or an equivalent) with the judicial exception, or merely includes instructions to implement an abstract idea on a computer, or merely uses a computer as a tool to perform an abstract idea;

- The additional elements only add insignificant extra-solution activity to the judicial exception; and;

- The additional elements do no more than generally link the use of a judicial exception to a particular technological environment or field of use.

- The “well-understood, conventional, and routine” analysis in Step 2B must consider all claim elements — even those previously deemed “insignificant.”

- The Examiner’s analysis during Step 2A specifically excludes consideration of whether the additional elements represent well-understood, routine, and conventional activity. Instead, this analysis is done in Step 2B.

- During Step 2A, examiners are to give weight to all additional elements, whether or not they are conventional, when evaluating whether a judicial exception has been integrated into a practical application.

- Elements found in Prong 1 to be part of the abstract idea, or elements found in Step 2A to be insignificant (or not contribute to the integration of the abstract idea into a practical application) are considered anew in determining whether the claim is “well-understood, conventional, and routine.”

- The office gives a helpful example of a data gathering step that may be considered as “insignificant extra-solution activity” under Step 2A, yet contribute the unconventionality (and thus, the overall inventive concept) of the claim.

Practice Tips

Given the case law and current USPTO posture, we provide the following practice tips for mitigating the applicability of §101 to a claim:

Application status: Pre-filing

- Thoroughly articulate the state of the art in the background section. Then in the detailed description, clearly articulate the improvement relative to the state of the art. This will help you argue later that the claims recite “significantly more” than what was known in the state of the art at the time of the invention.

- Conduct a patentability search to ensure improvement is accurately defined, and to ensure you understand the technical contribution provided by the invention.

- Consider in advance how you would argue the technical problem/technical solution test for inventive step in Europe – it is possible that the U.S. is headed in that direction for eligibility.

- Include alternative embodiments in the specification, or discuss other methods known in the art. This will help you demonstrate that the inventive concept does not have a preclusive effect on all approaches of an abstract idea.

- Support all claims in equal detail, in case you need to rely on your dependent claims. Provide detailed algorithms for all method steps claimed, in case they are interpreted under §112(f) as means/step-plus-function claims. This is especially applicable for software claims.

- Take advantage of the limitations inherent to means-plus-function claims. If fully supported in your specification, means-plus-function claims may provide enough of a specific implementation to overcome a §101 challenge. Plus, such claims may be viewed favorably outside the U.S.

- Integrate hardware or specialized computing devices into the steps of the claims. Demonstrate why the steps cannot be performed by humans.

- Draft claims to avoid classification into Tech Center 3600, which has an extremely low allowance rate compared to other software/electronics tech centers.

Application status: Pending

- Take advantage of the First Action Interview Pilot Program (FAIPP). For appropriate claims, you may want to argue that your claims do not preempt all uses of the abstract idea, such that the claims qualify for “streamlined analysis.” But if the Examiner issues an office action that does not use the streamlined analysis, the weight of your preemption argument is lessened. Use the FAIPP to argue for the stream- lined analysis early on, so that the Examiner can hear your arguments before he or she performs the full analysis.

- Recognize when the Examiner has not analyzed each and every claim as required by the Guidelines, or has not clearly identified the abstract idea(s) recited in the claims. Push back against the incompleteness of a rejection when appropriate. Use this to argue that a future rejection be made non-final.

- If the abstract idea is identified as a fundamental economic practice, present evidence showing that the concept is not fundamental. Argue that the claimed practice only exists because of the particular technical implementation.

- If the abstract idea is identified as a method of organizing human activity, argue that the claims cannot be performed by a human and/or require a specific machine implementation to operate.

- Introduce expert declarations rebutting the Examiner’s positions. Focus on the scope of the abstract idea, or the inventiveness of the “something more.” This also has the benefit of entering expert evidence into the record during prosecution, which is generally easier than trying to enter expert evidence during an inter partes process.

- If an abstract idea has been identified by the examiner, confirm that the examiner is identifying an appropriate abstract idea category. Moreover, even when an abstract idea is found, ensure that the examiner is properly giving weight to all claim limitations when determining whether the abstract idea is integrated into a practical application.

- Novelty of the alleged “abstract idea” and any other extra-solution activity can now contribute to the unconventionality of the claim as a whole, such that the claim survives a patent-eligibility challenge.

- §101 law is in great flux. Keep a continuation pending to update the claims as the law changes.

Application status: Issued Patent

- Analyze claims for §101 issues prior to enforcement.

- File a narrowing (or broadening, within 2 years) reissue to revise claims through the USPTO.

- Must argue that the patentee claimed more or less than he or she had the right to claim. Possibly argue that the claim amendments remove a potential preemption of an abstract idea.

- Enter an ex parte reexamination using supplemental examination. While §101 is usually not a valid ground for filing an ex parte reexam, there is a special carve-out for ex parte reexams resulting from supplemental examination. If a patentee requests supplemental examination based on §101, the USPTO will determine whether a substantial new question of patentability (SNQ) exists. If so, the USPTO will institute an ex parte reexamination to address the SNQ.

This article appeared in the 2020 Patent Prosecution Tool Kit.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates