Introduction

Imagine sitting in a conference room with your carefully crafted set of questions for a deposition, and you are exploring the basis for an opposing expert’s opinions. But instead of giving thoughtful answers, the expert simply states “I don’t have an opinion on that” on the basis that the material was not explicitly discussed in her declaration. Or maybe the expert simply regurgitates her written testimony or answers a different (unasked) question. Practitioners will likely tell you that such scenarios, and a range of other recalcitrant, evasive, and unreasonably obstructive behavior have recently become too common in USPTO Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) depositions. Of course, no attorney wants their client’s expert to actively help an opposing counsel, who is generally seeking to craft admissions that will undermine the expert’s testimony. But there needs to be limits on inappropriate behavior, or at least some consequences for bad behavior. Otherwise, the ability to cross-examine witnesses loses any meaning and becomes a waste of resources, while undermining the effectiveness and integrity of the PTAB process.

Almost every major brief filed in a post-grant proceeding is accompanied by an expert declaration, and these declarations support the technical and factual arguments made in the brief. Moreover, expert analysis and testimony are more often than not critical evidence that the PTAB will use in reaching a decision regarding the patentability of a set of claims. Therefore, effective examination and rebuttal of expert testimony can be key to crafting responsive pleadings and eventual success in defending or challenging patents before the PTAB. Conversely, parties have strong incentives to have their experts defend their testimony as aggressively as possible.

As discussed below, parties currently have limited recourse to address bad behavior by witnesses. The Board pays little attention to witness behavior, essentially never strikes or excludes testimony, and rarely mentions expert behavior as a factor in diminishing witness credibility. We suggest two practical solutions to curb expert bad behavior: more regular live testimony of witnesses in front of PTAB judges, and the normalization of more severe consequences for unreasonable behavior during deposition.

There is very little cost associated with a witness’s bad behavior

One potential avenue of recourse for parties encountering expert bad behavior is a motion to strike the witness’s direct testimony. However, there is little reason to believe that such an approach will be fruitful without change.1 Our searching2 identified 164 motions to strike that related to expert testimony for which the Board issued a decision. Of those motions, the Board granted or partially granted only 21. And within the group of 21, there were no decisions in which the Board struck expert testimony based on behavior during deposition. Rather, almost all of the successful motions to strike related to expert testimony as improper sur-reply evidence, or declarants that were not made available for deposition. Instead of being receptive to motions to strike expert testimony, the Board generally maintains that witness behavior is part of a credibility determination that goes to the weight, rather than the admissibility of the declaration testimony.3

Given that the Board often indicates that it prefers to analyze the weight to be given to testimony, we have looked for evidence that witnesses’ bad behavior during deposition has resulted in the witness losing credibility with the Board and harming the case of the proponent of the testimony. However, there is little evidence that this occurs, as the Board rarely mentions witnesses’ demeanor as a factor in reaching a final decision. Even when the Board does address demeanor, the most common result is that the Board avoids the issue. For example, in Intel Corp. v. Pact XPP Schweiz AG, the Board dismissed assertions that an expert was “improperly recalcitrant” and “demonstrated a lack of knowledge of the subject matter” by noting that the testimony in question was not related “to the portions of [testimony] . . . on which we rely for our decision.”4 Similarly, when faced with assertions that a witness was “nonresponsive” and gave “evasive answers at deposition [that] undermine his credibility,” the Board responded only by asserting that it is capable of “assign[ing] the appropriate weight to be accorded evidence.”5

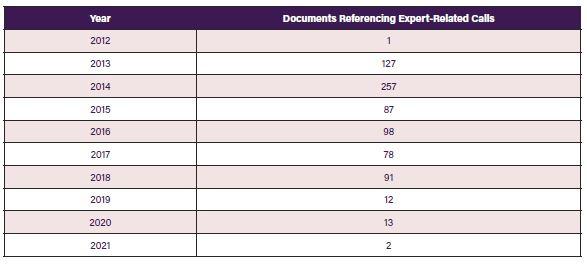

An alternative avenue of recourse is for parties to contact the Board directly during the course of the deposition and ask for relief, e.g., in the form of witness instructions or additional deposition time. While tracking the frequency of such calls is difficult because they often are not reflected in the written record of a case, we performed searches for documents that reference conference or telephone calls relating to experts.6 As shown in the chart on pg. 31, such calls were common during the first few years of PTAB practice, but the number has drastically reduced in recent years. We posit that this difference is at least in part due to a lack of successful results from those calls.

What can be done to curb bad behavior?

In view of the limited recourses for witness bad behavior, there is a need for new or improved mechanisms to deter such behavior. We suggest that there are already at least two mechanisms in place, both of which could serve that purpose if appropriately strengthened by the PTAB and used more often by PTAB practitioners.

First, we recommend facilitating more frequent live testimony of witnesses in front of PTAB judges. As noted by the PTAB’s Trial Practice Guide, “[c]ross-examination may be ordered to take place in the presence of an administrative patent judge, which may occur at the deposition or oral argument.”7 The Board recognizes that such live testimony can be useful when “the Board considers the demeanor of a witness critical to assessing credibility.”8 Such live testimony could be a solution to bad witness behavior because it will provide judges with a more complete view of witness demeanor than snippets of testimony provided in briefs. Moreover, witnesses would be motivated to at least appear to be reasonable and honest in front of the case’s decision-makers. And witnesses may be less likely to behave badly in a deposition if they know such testimony could be used for impeachment purposes during live cross-examination.

However, for live testimony to have any appreciable impact on post-grant proceedings, it must become much more commonly used. As noted in the Board’s precedential K-40 Electronics decision, the Board allows such live testimony only “under very limited circumstances.”9 That case noted that two factors that would favor live testimony are whether the witness’s testimony “may be case dispositive” and whether the witness is a fact witness.10 Live expert testimony has been discouraged because “the credibility of experts often turns less on demeanor and more on the plausibility of their theories.”11 In view of this limiting standard, live testimony has been requested in only 20 different cases, and granted in only three, during the lifetime of post-grant proceedings.12 Therefore, establishing a more plausible and regular path to having live testimony is necessary for it to serve the purpose of deterring bad behavior. One plausible path is to allow for a limited time frame in which parties may question witnesses on pre-selected issues that are “case dispositive” as part of the oral arguments in a case. This would allow for judges to observe demeanor first-hand. With this in mind, it is also incumbent on PTAB practitioners to aggressively request live testimony when inappropriate and overly evasive expert behavior occurs.

Second, the PTAB should normalize striking or expunging of testimony in extreme cases of bad behavior, or perhaps more regularly provide commentary indicating when witness testimony is given less weight in view of unreasonable behavior during deposition. It is understandable that the PTAB is hesitant to strike expert testimony in view of the extreme prejudice to parties if central evidence supporting their case is struck or expunged. But exemplary cases demonstrating that there is a line beyond which behavior is not tolerated could prove a powerful deterrent to at least the most extreme behaviors. Again, it is incumbent upon PTAB practitioners to bring this type of bad behavior to the PTAB’s attention, so the PTAB can better appreciate the extent of the issue.

Implementing either of these solutions could provide a strong incentive for witnesses to behave in a more reasonable and honest manner during deposition, further strengthening the effectiveness and integrity of the PTAB process.

1. Patent Trial and Appeal Board Consolidated Trial Practice Guide November 2019, pp. 80 (noting that striking an “entirety or a portion of a party’s brief is an exceptional remedy”).

2. We used DocketNavigator.com to identify motions to strike.

3. See, e.g., 10X Genomics, Inc. v. The University of Chicago, IPR2015-01157, Paper 30, p. 2 (P.T.A.B. May 26, 2016) (“The panel noted that any non-responsiveness of a witness to questioning during cross-examination would go to the weight given to that witness’s direct testimony, but that a motion to strike the testimony altogether was not warranted).

4. IPR2020-00540, Paper 30, p. 11 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 8, 2021).

5. Intel Corp. v. Pact XPP Schweiz AG, IPR2020-00542, Paper 31, pp. 19, 28-29 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 7, 2021).

6. There are a variety of reasons for which a Board call may reference experts, so this data is not entirely reflective of just calls related to experts’ bad behavior. Nevertheless, the trend is clear—there have been a diminishing number of Board calls about experts.

7. Patent Trial and Appeal Board Consolidated Trial Practice Guide November 2019, pp. 31-32.

8. Id. at 31-32; see also K-40 Electronics, LLC v. Escort Inc., IPR2013-00203, Paper 34, p. 2 (P.T.A.B. May 21, 2014) (precedential).

9. K-40 Electronics, LLC, IPR2013-00203, Paper 34, p. 2.

10. Id. at 2-3.

11. Id. at 2-3.

12. Live testimony has been allowed in IPR2013-00203 (Paper 34), IPR2018-01524 (Paper 40), and IPR2015-00977 (Paper 32).

This article appeared in the 2021 PTAB Year in Review: Analysis & Trends report. To view our graphs on Data and Trends, please click here.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates