On January 14, 2022, Hermès International and Hermès of Paris, Inc. (“Hermès”) sued digital artist Mason Rothschild in the Southern District of New York for creating and selling “MetaBirkins,” a collection of NFTs tied to digital art depicting tote bags inspired by the iconic Birkin bag. Hermès alleges that Rothschild’s art appropriated its BIRKIN trademark rights and constitutes unfair competition, trademark infringement, and dilution by blurring. This case gives rise to the following questions for digital artists and brand owners alike: (1) when does Appropriation Art infringe the original creator’s trademark rights and (2) does the non-fungible token (“NFT”) medium influence the analysis?

1. Appropriation Art

Appropriation art borrows or copies an iconic or universally recognizable work and reframes it. A famous appropriation artist might come to mind: Andy Warhol. Warhol is known as the painter of green Coca-Cola bottles, the man who elevated Campbell’s soup cans into art, the iconic pop artist whose works are displayed worldwide – and, more recently, the artist whose estate has been litigating intellectual property suits.

The use of appropriation in art certainly raises copyright issues, and has led to a number of copyright infringement lawsuits. Courts do not find every example of appropriation art to infringe the original work they imitate, such as Jeff Koons’ Niagara, 2000 painting that was inspired by Andrea Blanch’s copyrighted photograph, Silk Sandals by Gucci. On the other hand, courts have found some examples – most notably, Andy Warhol’s “Prince Series” – not transformative enough to qualify as fair use but are instead substantially similar to the appropriated original image and infringe.1 The Second Circuit’s application of the fair use test (particularly the “transformative use” element) to the “Prince Series” has one conceptual artist, Barbara Kruger, asking the Supreme Court to look into whether that application could destroy the art world’s longstanding practice of incorporating preexisting material into new works of art, thus hindering copyright law’s goal of promoting creativity. In an amicus brief filed on January 10, 2022, days before Hermès filed its lawsuit against Rothschild, Kruger argues that the Second Circuit’s fair use test is undefined and threatens art that builds on preexisting work that might have “little change in outward form” but is “far from lacking creativity.”2

The fair use doctrine, however, may be less relevant when appropriation art incorporates a trademark. See Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Inc. v. Pussycat Cinema, Ltd., 467 F. Supp. 366 (S.D.N.Y.), aff’d, 604 F.2d 200 (2d Cir. 1979) (There, the Second Circuit did not reach the question of whether the “fair use” doctrine is applicable to trademark infringements.) When art appropriates a trademark, First Amendment protections of freedom of expression are implicated, and the more relevant test may be the balancing test articulated by the Second Circuit in Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994, 999 (2d Cir. 1989).

Under the Rogers test, an artistically expressive use of a trademark may by protected by the First Amendment, and therefore will not constitute trademark infringement “unless the use of the mark has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever, or, if it has some artistic relevance, unless it explicitly misleads as to the source or the content of the work.” E.S.S. Entertainment 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc. 547 F.3d 1095 (9th Cir. 2004); see also Rogers, 875 F.2d at 999. Thus, whether the First Amendment is implicated by an artist’s work requires a balancing test of various considerations, including the level of artistic relevance, risk of the art explicitly misleading consumers as to source or content, danger of suppressing artistically relevant and ambiguous titles, and the restriction of expression. Id. at 1001. The Fifth, Sixth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits also follow the Rogers test.

Recently, however, a federal district court in the Tenth Circuit declined to follow the Rogers test, which it viewed as having the potential to destroy the value of trademarks. See Stouffer v. Nat’l Geographic Partners, LLC, 400 F. Supp. 3d 1161, 1178 (D. Colo. 2019) (“…it creates the risk that senior users of a mark end up with essentially no protection every time the junior user claims an artistic use.”) Accordingly, the district court adopted a new test, which considers whether a junior user had “genuine artistic motive for using the senior user’s mark.” Id. at 1179. Unlike in the Rogers test, the artistic relevance of a work in question is not a threshold inquiry, but among the following factors considered by the “Genuine Artistic Motive” test. Id. at 1179.

- Do the senior and junior users use the mark to identify the same kind, or a similar kind, of goods or services?

- To what extent has the junior user “added his or her own expressive content to the work beyond the mark itself”?

- Does the timing of the junior user’s use in any way suggest a motive to capitalize on popularity of the senior user’s mark?

- In what way is the mark artistically related to the underlying work, service, or product?

- Has the junior user made any statement to the public, or engaged in any conduct known to the public, that suggests a non-artistic motive?

- Has the junior user made any statement in private, or engaged in any conduct in private, that suggests a non-artistic motive?

2. Hermès and the BIRKIN bag

Hermès owns over a dozen registered trademarks, including one for the word mark BIRKIN that has been on the Principal Register since September 6, 2005, and one for the three-dimensional shape of a BIRKIN bag (shown below) that has been on the Principal Register since 2011 (“the BIRKIN marks”).

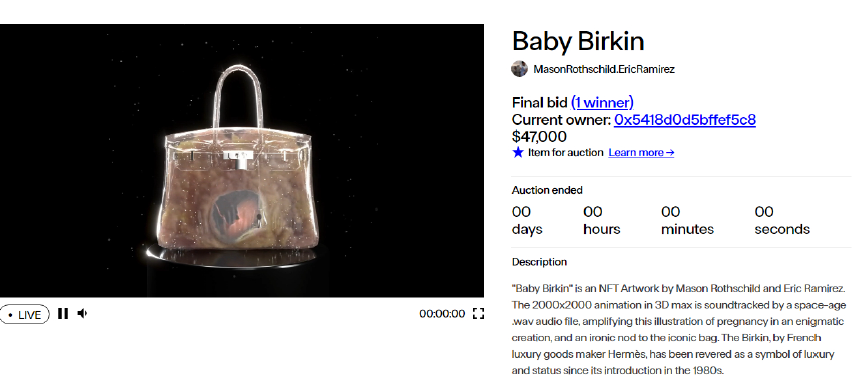

The first line of Hermès’s near fifty-page complaint cites Rothschild’s own interview with Yahoo Finance Live where he states: “there’s nothing more iconic than the Hermès Birkin bag.” Rothschild goes on to explain that his MetaBirkins NFTs collection is an experiment to create an illusion that “has in real life as a digital commodity.” Rothschild mentions how NFT’s strength is the strong, supportive community. That support is evidenced by the $23,500 sale of his Baby Birkin NFT that features a BIRKIN bag 40 weeks pregnant with a child – and is more expensive than the real Hermès bag. It resold for about double that price.

See Exhibit R to Compl.

The total volume of sales for the MetaBirkins NFTs is over $1 million.

Hermès’s complaint acknowledges that, while a digital image connected to an NFT “may reflect some artistic creativity” like a T-shirt or greeting card, referring to the work as “art” does not automatically implicate First Amendment protection to avoid liability for appropriating another’s trademark and its goodwill. Ironically, Rothschild himself has discussed the problem of infringement in the form of counterfeit NFTs. Fake MetaBirkins NFTs went for sale before his collection even dropped and, according to Rothschild, about $40,00 in volume of counterfeit MetaBirkins NFTs were bought. Rothschild even tweeted about this problem and mentioned that he was working with OpenSea, the online platform through which he originally sold the NFTs, to verify his items. After Hermès notified Rothschild and OpenSea of the infringing use of its mark, OpenSea quickly removed the MetaBirkins NFT collection from its platform. Rothschild continues to sell his NFT collection on Rarible.

Hermès argues that this very issue – Rothschild’s own counterfeit allegations for his NFTs – weighs against the fair use defense in the present trademark action. A fair use defense does not provide protection from liability if the defendant uses the allegedly infringing mark as the defendant’s own trademark or source of goods. In other words, since Rothschild is attempting to use “MetaBirkins,” which he claims trademark rights in, as a source identifier for his NFTs, Rothschild can’t then use the fair use defense in the trademark infringement claim by Hermès.

Rothschild took to Instagram to explain the litigation strategy of his counsel: that his MetaBirkins NFTs are works of art that may receive special protection under the First Amendment, like the works of Warhol.3 On February 9, 2022, Rothschild filed a motion to dismiss the Hermès complaint. In the motion’s preliminary statement, Rothschild describes the MetaBirkins series as a “unique, fanciful interpretation of a Birkin bag” that comments on the animal cruelty inherent in Hermès’ manufacture of leather bags, and that an image or NFT “carr[ies] nothing but meaning.” Rothschild’s motion then explicitly invokes the Rogers test to argue that speech which is sold applies to NFTs.4 While Rothschild’s post made clear that he does not believe the NFT medium changes “the fact that it’s art,” his previous interviews emphasize how the success of his work comes from the unique factors and circumstances of NFTs and the metaverse. In his Motion to Dismiss, Rothschild refines his position by arguing that the NFT medium “makes no difference” to the application of First Amendment legal principles and that “meta” refers to the metaverse where he sells the NFTs as well as the type of commentary he makes on the Birkin bag.

When a case involving trademark infringement by NFTs makes it to the stage of opinion writing, it will be telling what weight a court gives to the presence – or absence – of a trademark registration covering virtual goods and/or services, and how the NFT medium impacts the infringement analysis. Furthermore, since NFTs include blockchain technology that keeps track of transaction records, which can be configured to pay the artist a percentage of secondary sales of the NFT, it will be interesting to see whether the court will allow a bona fide purchaser to keep and/or later resell an NFT that is found to infringe another’s trademark. This question may implicate Copyright Law’s first-sale doctrine (17 U.S.C. § 109), which permits a purchaser of a legal copy of a copyrighted work from the copyright holder to display, sell, or otherwise dispose of that particular copy. Here, the tension lies between the trademark owner’s rights being infringed by an unapproved sale of an allegedly infringing NFT and a bona fide purchaser’s rights under the first sale doctrine. Inevitably, courts will begin the analysis by looking to see what, if any, rights were transferred to a purchaser along with the NFT purchase, as well as whether the NFT included a smart contract enabling the artist to continue to reap the benefits of future sales of the NFT.

3. Takeaways

The “Genuine Artistic Motive” test and other recent case law might suggest a general shift away from granting appropriation art special protection under the First Amendment.5 However, regarding Rothschild’s MetaBirkins NFTs, the Southern District of New York is bound to apply the Rogers test, potentially leading to a finding that Rothschild’s use of the BIRKIN marks has “some artistic relevance.” (The level of artistic relevance is extremely low – “merely must be above zero.” E.S.S., 547 F.3d at 1100.)

Whether the court will find that Rothschild’s use of the BIRKIN word marks does not explicitly mislead consumers as to the source of the MetaBirkins NFTs is less clear – particularly as the Rogers test does not extend to use of the trademark within a new brand name, as is done with “MetaBirkins NFTs.” Additional factors also weigh in favor of a court finding consumer confusion and thus, trademark infringement: the evidence of counterfeit NFT sales for MetaBirkins NFTs, open discussions regarding the intention of working off the BIRKIN brand, and the purpose of collecting a digital commodity of the original bag. On the other hand, Rothschild may argue that its online disclaimer and hashtag #NotYourMothersBirkin make clear that his MetaBirkins NFTs are not “affiliated, associated, authorized, endorsed by, or in any way officially connected with the[sic] HERMES,” to prevent consumer confusion – although it is questionable whether these arguments will prove persuasive.

This is just the next of likely many impending intellectual property disputes involving NFTs. Most recently, Nike sued StockX for selling NFTs depicting images of Nike footwear, which may then be redeemed in exchange for the physical product corresponding to the image depicted in the NFT.6 As we know from Facebook’s jump to the metaverse, a virtual world is being born where people can showcase and sell digital forms of art and property in the form of NFTs, purchased through blockchain technology. NFTs can even be sold, resold, and otherwise transacted secretly. While some companies are filing new trademark applications covering virtual versions of their goods in light of the growing popularity surrounding NFTs,7 others are registering their NFTs with the U.S. Copyright Office.8 It remains to be seen whether and how entities will use U.S. design patents to protect the appearance of their virtual goods.

Appropriation artists would therefore be wise to conduct a trademark clearance search for the title and/or subject of their next artwork if inspired by another’s trademark or trade dress. As evidenced by Nike, brand name companies are entering the metaverse and are seeking protection of their trademarks in connection with virtual goods and NFTs. Therefore, artists can reasonably assume that brand companies will police uses of their marks in both the virtual world and the real world for possible infringement. Some NFT platforms already provide formal processes for submitting IP takedown requests. Adding a disclaimer to artwork that appropriates a trademark or trade dress to disassociate it with the trademark/trade dress owner may help to avoid misleading customers as to source of the artwork – although, as history has shown, appropriation art inspired by an iconic trademark or product design is likely to incite an enforcement action and litigation.

[1] Ivy C. Estoesta, Art Imitating Art?, MarkIt to Market®, www.sternekessler.com/news-insights/publications/art-imitating-art (March 2021), referring to Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 111 (9th Cir. 2018) and Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26, 54 (2nd Cir. 2021).

[2] Tiffany Hu, Barbara Kruger Asks Justices To Mull Warhol Fair Use Ruling, Law360, www.law360.com/articles/1454206 (Jan. 12, 2022), referring to Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc. v. Goldsmith., case number 21-869.

[3] Andrew Karpan, Hermes Says Designer Is Selling Blurry, Knockoff Birkin NFTs, Law360, www.law360.com/ip/articles/1455919/hermes-says-designer-is-selling-blurry-knockoff-birkin-nfts (Jan. 18, 2022).

[4] See, e.g., E.S.S. Entertainment 2000, Inc. v. Rock Star Videos, Inc., 547 F.3d 1095 (9th Cir. 2008) (holding that use of plaintiff’s PLAY PEN logo and trade dress in Rock Star Video’s Grand Theft Auto video game did not infringe the plaintiff’s trademark rights); University of Alabama Board of Trustees v. New Life Art., Inc., 683 F.3d 1266 (11th Cir. 2012) (holding that the defendant artist’s depiction of University and athletic trademark logos in documentary-style paintings of famous plays did not infringe the University’s trademarks); Mattel, Inc. v. MCA Records, Inc., 296 F.3d 894 (9th Cir. 2002) (holding that the use of plaintiff’s BARBIE trademark in defendant’s song title Barbie Girl did not constitute trademark infringement).

[5] See Gordon v. Drape Creative, Inc., 909 F.3d 257 (9th Cir. 2018). There, the Ninth Circuit found that defendant’s greeting cards including plaintiff’s registered mark HONEY BADGER DON’T CARE are expressive works having some artistic relevance under the Rogers test, but remanded for further consideration on whether defendant’s use of plaintiff’s mark is explicitly misleading.

[6] Nike, Inc. v. StockX LLC, 22-cv-983, Compl. (S.D.N.Y. February 3, 2022).

[7] Kathleen Wills, “Say What Again?”: Pulp Fiction Shows us Where NFTs Meet Trademark Law, MarkIt to Market® (Nov. 2021) (explaining the applicability of trademark legal principles to NFTs).

[8] See U.S. Copyright Reg. No. VAu001448454 to NFT Canna Club Inc. for its Nugg artwork; see also U.S. Copyright Reg. No. VAu001448496 to Simeon Basil for its NFT Bluebird of Happiness Collection.

This article appeared in the February 2022 issue of MarkIt to Market®. To view our past issues, as well as other firm newsletters, please click here.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates