Summary

The USPTO Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) has increasingly used its discretionary denial authority in recent years. Although the PTAB’s discretion under 35 U.S.C. § 314(a) and Fintiv grabbed many headlines in 2021, the PTAB’s discretion under 35 U.S.C. § 325(d) can be equally fatal to an America Invents Act (AIA) petition. This articles focuses on the PTAB’s discretion under Section 325(d).

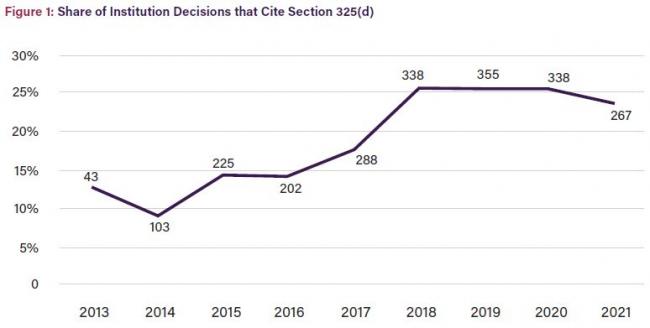

The PTAB considers exercising its discretion under Section 325(d) when petitions raise the same or substantially the same prior art or arguments previously presented to the Office. Over the last four years, the PTAB cited Section 325(d) in about 25% of its institution decisions—significantly more than the share of institution decisions issued from 2013 to 2017 (see Figure 1 below). Somewhat under-the-radar, the PTAB’s Section 325(d) jurisprudence has grown to include three precedential and eleven informative decisions.

Practitioners must understand the important, and fact specific, analysis that the PTAB applies when evaluating whether to exercise discretion under Section 325(d). This is especially true because we believe the PTAB’s jurisprudence on this issue, which is firmly rooted in the statutory text, is here to stay. By contrast, Fintiv’s fate is uncertain, as 2022 will likely bring a new Director of the USPTO who can abrogate Fintiv, as well as various legal challenges working their way through the federal courts and proposed legislation aimed at reining in the Director’s discretion and potentially abolishing Fintiv.

Because discretion under Section 325(d) is a threshold issue that the PTAB addresses at institution, petitioners should proactively address the considerations of the PTAB’s applicable framework. Indeed, merely raising an objectively meritorious ground of unpatentability may not be enough for petitioners to avoid Section 325(d) denial. On the other hand, when confronted with art or arguments previously presented to the Office, patent owners should take full advantage of a Section 325(d) defense to leverage the PTAB’s willingness to exercise its discretion. Accordingly, a comprehensive understanding of the Section 325(d) framework is necessary to formulate winning strategies to either obtain or defend against institution. Here, we dissect the PTAB’s Section 325(d) framework and explain how parties have either avoided or encouraged Section 325(d) denial.

The Advanced Bionics Two-Part Framework and Its Impact

On March 24, 2020, the PTAB designated Advanced Bionics, LLC v. Med-El Elektromedizinische Geräte GMBH1 and two sections of Oticon Medical AB v. Cochlear Ltd.2 as precedential to provide balanced guidance on how the PTAB exercises its discretion under Section 325(d). While presented with the same issue—whether the same or substantially the same art was previously presented to the Office—the PTAB reached opposite conclusions in these decisions. In Advanced Bionics, the PTAB exercised its discretion to deny institution under Section 325(d), finding that the newly asserted art by the petitioner was the same or substantially the same as art previously presented to the Office.3 Conversely, in Oticon Medical, the PTAB determined that the newly asserted art was not the same or substantially same as art previously presented to the Office, and declined to exercise its discretion.4 Thus, both petitioners and patent owners can glean helpful insight from these decisions.

In Advanced Bionics, the PTAB established the following “two-part framework” for evaluating whether to exercise discretion under Section 325(d):

- whether the same or substantially the same art previously was presented to the Office or whether the same or substantially the same arguments previously were presented to the Office; and

- if either condition of the first part of the framework is satisfied, whether the petitioner has demonstrated that the Office erred in a manner material to the patentability of challenged claims.5

The Advanced Bionics two-part framework streamlines the process for applying the six non-exclusive factors enumerated in Becton, Dickinson—the PTAB’s first precedential decision interpreting Section 325(d).6Becton, Dickinson factors (a), (b), and (d) pertain to whether the same or substantially the same art or argument was previously presented to the Office.7 And Becton, Dickinson factors (c), (e), and (f) relate to whether the petitioner has demonstrated material error by the Office.8 Institution decisions over the past year provide insight on how the PTAB applies the Advanced Bionics framework and, thus, potential strategies for both petitioners and patent owners.

Part I of the Advanced Bionics Framework

The first part of the Advanced Bionics framework evaluates (1) whether the same or substantially the same art previously was presented to the Office, and (2) whether the same or substantially the same arguments previously were presented to the Office.

Whether the same or substantially the same asserted art or argument was previously presented to the Office covers a broad range of proceedings, including examination of the underlying patent application, reexamination of the challenged patent, a reissue application for the challenged patent, and other AIA post-grant proceedings.9 The PTAB may also look at applications directly related to the challenged patent, such as a parent application.10 Previously presented art includes art cited by the examiner and art provided to the Office by the applicant (e.g., in an Information Disclosure Statement). 11

- Comment: In assessing the similarity of asserted art to previously presented art, practitioners should also consider proceedings involving applications related to the challenged patent.

There is typically no dispute that the first part of the framework is satisfied when the asserted art was either cited by the examiner or provided to the Office by the applicant. But patent owners should not assume that the PTAB will sua sponte exercise its discretion if only some of the art was previously presented to the Office.

- Patent Owner Tip: The PTAB may decline to exercise its discretion when the patent owner does not dispute petitioner’s assertions that previously presented art was not substantively considered during prosecution or that newly cited art is not cumulative to previously presented art.12

While patent owners typically must show that the asserted art is the same or substantially the same as previously presented art to seek discretionary denial, petitioners should proactively address this issue even before filing the petition. Petitioners can increase the likelihood of avoiding discretionary denial under Section 325(d) by relying on newly cited art as much as possible. Asserting new art—even if combined with previously presented art—forces the PTAB to further determine whether the newly asserted art is cumulative to the previously presented art and whether the previously presented art is being applied in a different way than it was when previously considered, before moving to the second part of the framework.

- Petitioner Tip: If the strongest prior art was previously presented to the Office (e.g., during prosecution), consider combining the previously presented art with new art to present a new combination for the PTAB to evaluate.

Indeed, the first part of Advanced Bionics framework may not be met even when one piece of asserted art was previously presented to the Office.13 In declining to exercise its discretion to deny institution, at least one PTAB panel has held that “[t]he fact that one piece of art from the combination was previous previously presented and/or argued to the Office alone is insufficient to satisfy the first prong of Advanced Bionics two-part test.”14 This especially applies when the previously presented art is used “in a minor capacity” with newly cited art, such as using newly cited art as the primary reference and previously presented art as the secondary reference.15 Thus, combining previously presented art with new art may not satisfy the first part of the Advanced Bionics test, persuading the PTAB to decline exercising its discretion.

- Patent Owner Tip: Do not assume that the first part of the Advanced Bionics framework is satisfied because the petition asserts one or more references previously presented to the Office; consider arguing that each newly asserted reference is substantially the same as previously presented art.

If a reference was not previously presented to the Office or if a previously presented reference is combined with new art, further analysis is needed before proceeding to the second part of the framework. That is, the PTAB must determine whether the asserted art is “substantially the same” as art or arguments previously presented to the Office.16 This highly factual inquiry may be informed by evaluating Becton, Dickinson factors (a), (b), and (d).17

The PTAB deems newly asserted art “cumulative” when the art’s relevant teachings provide nothing more than what was taught by previously presented prior art.18 This may include teachings that are “structured substantially identically to those previously considered by the Office” and “relied on for the same proposition” as previously considered art.19 Notably, the teachings between the newly asserted art and previously presented art do not need to “be identical or entirely cumulative, only [] substantially same” to satisfy the first prong of the Advanced Bionics framework.20 Nonetheless, showing that newly asserted art is cumulative to previously presented art can be a rigorous task for the patent owner.

When facing an unpatentability ground based on a combination of new and previously presented art, patent owners should evaluate whether the relevant teachings of the new art present nothing more than what was previously considered by the Office. Given the detailed nature of this inquiry, patent owners should consider identifying any overlapping material similarities between the new art and the previously presented art. For example, a chart that maps corresponding structures and functions of the new art to previously presented art can help the PTAB easily identify the similarities between the teachings.

Although fact intensive, the PTAB’s Section 325(d) jurisprudence provides helpful guideposts when performing this analysis. Oticon Medical, for example, demonstrates that the PTAB does not consider newly asserted art to be substantially the same as previously presented art when disclosing “different structures that serve different purposes.”21 PTAB panels have also declined to find a combination of new and previously presented art to be substantially the same when the new art addresses shortcomings of the previously presented art “in a different manner than the rejections made by the Examiner.”22

Nevertheless, petitioners cannot assume that newly asserted art is immune from discretionary denial, particularly when the newly asserted art includes teachings analogous to the previously presented art.23 As part of their due diligence, petitioners should thoroughly review the prosecution history to determine if any newly asserted art is cumulative to previously presented art. And petitioners should distinguish their unpatentability arguments from rejections provided by the Office during prosecution.

For example, when relying on the combination of new and previously presented art, petitioners should consider presenting obviousness rationales that are different than the motivations used by the examiner in any obviousness rejections. And if the prosecution history identifies any deficiencies in the previously presented art, consider combining new art that directly addresses those shortcomings.

- Petitioner Tip: Consider distinguishing the asserted unpatentability ground(s) from rejections raised during prosecution by including different rationales for combining references or relying on overlooked disclosures in previously presented art.

Part II of the Advanced Bionics Framework

If the petition presents the same or substantially the same art or arguments, the PTAB turns to the second part of Advanced Bionics framework—whether the Office erred “in a manner material to the patentability of the challenged claims.”24 The PTAB applies Becton, Dickinson factors (c), (e), and (f) to determine if there was a material error.25

Under Part II of the framework, petitioners must show that the Office erred in a manner material to the patentability of challenged claims. Petitioners’ strategy for demonstrating an error by the Office should be guided by the level of detail in the record of the Office’s previous consideration of the prior art.

When the record of the Office’s previous consideration of the art is silent or not well-developed, simply showing that the previously presented art likely discloses a contested limitation may be enough to persuasively demonstrate a material error.26 For example, some PTAB panels have declined to exercise discretion when the prosecution history provides little insight into the examiner’s evaluation of the prior art and the petitioner demonstrates with a reasonable likelihood that the previously presented art discloses the allegedly patentable features.27 This may occur when the underlying application was allowed without any substantive office actions or when the previously presented art was one of many references cited in an Information Disclosure Statement but not applied in an office action.28 Because the PTAB tends to focus more on the merits of the petition when the prosecution record is not well-developed, petitioners should consider linking their arguments against discretionary denial with the merits of their unpatentability grounds.

- Petitioner Tip: Consider emphasizing that the Office overlooked the pertinence of the previously presented art, as demonstrated in the unpatentability grounds of the petition, when the record of the Office’s previous consideration of the art is silent or not well-developed.

In these more clear-cut situations of material error, petitioners should consider keeping arguments against discretionary denial succinct, devoting more of their word count to the merits of the unpatentability grounds.

Similarly, patent owners should consider coordinating their arguments for discretionary denial with their arguments on the merits when the prosecution record is silent or not well-developed. For example, patent owners may look to the notice of allowance (or elsewhere in the prosecution history) to determine if the examiner indicated allowable subject matter of the issued claims. If so, patent owners might emphasize that the previously presented art does not disclose or suggest the limitations that the examiner found missing in the prior art.29

- Patent Owner Tip: Determine if the examiner indicated in the prosecution history any limitations that were distinguishing features and consider emphasizing that the previously presented art does not disclose those limitations that the examiner found missing from the prior art.

On the other hand, when the prosecution history provides a detailed account of the examiner’s evaluation of the prior art, petitioners must show persuasively that the examiner “erred in the evaluation of the prior art, for example, by showing that the [e]xaminer misapprehended or overlooked specific teachings in the relevant prior art such that the error by the Office was material to the patentability of the challenged claims.”30 In this scenario, the burden on the petitioner is significant. Simply presenting a different interpretation of previously presented art is unlikely to convince the PTAB to institute review.31 Indeed, the PTAB in Advanced Bionics instructed that “[i]f reasonable minds can disagree regarding the purported treatment of the art or arguments, it cannot be said that the Office erred in a manner material to patentability.”32 And failing to proactively identify overlooked disclosure in the previously presented art diminishes petitioners’ chances of showing a material error.33 Rather, petitioners should consider identifying the art considered by the examiner in the prosecution history and explaining any overlooked or misapprehended disclosure that was material to patentability.

- Petitioner Tip: When the record provides a detailed account of the Office’s evaluation of the prior art, consider identifying and explaining any overlooked or misapprehended disclosure.

One example is demonstrating that the examiner overlooked an embodiment of an asserted reference that clearly shows the limitation at issue.34 Another example is demonstrating that the previously presented art was not “extensively evaluated for the same purposes” that the petitioner relies upon the reference in the petition.35 Petitioners may also show that the Office committed “an error of law,” for example, by misconstruing a claim term that impacted the patentability of the challenged claims.36 By implementing these strategies, petitioners may reduce the likelihood the PTAB exercises its discretion to deny the petition under Section 325(d).

Section 325(d) Applies to Ex Parte Reexaminations

Another option for challenging the validity of a patent is ex parte reexamination requests. The Federal Circuit’s recent holding in In re Vivint Inc., demonstrates that the Office may exercise its discretion under Section 325(d) to deny reexamination requests that assert the same or substantially same art as prior post-grant proceedings.37 Parties to reexamination proceedings should thus evaluate whether and how Section 325(d) affects their positions.

Background

Alarm.com filed fourteen inter partes review (IPR) petitions against four patents asserted by Vivint.38 The PTAB denied three IPR petitions against Vivint’s ’513 patent and one IPR petition against Vivint’s ’091 patent under Section 325(d) for abusive filing.39 More than a year later, Alarm.com copied grounds from the ’091 patent petition into a request for reexamination of the ’513 patent.40 The Office granted reexamination and denied Vivint’s petitions seeking dismissal under Section 325(d).41 In denying Vivint’s petitions, the Office purported that it lacked the authority to consider petitions filed after the Reexamination Order and explained that Vivint could have sought a waiver to petition the Office before the Reexamination Order.42 The Office ultimately rejected all the claims of the ’513 patent in reexamination.43 Vivint appealed, arguing that Alarm.com did not present a substantial new question of patentability.44

The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit found that Alarm.com did present a substantial new question of patentability because the grounds repeated from the IPR petitions were never considered on the merits, since the PTAB denied institution of the IPRs.45 But the Federal Circuit held that Section 325(d) discretionary denial applies to reexamination proceedings, even if the request presents a substantial new question of patentability.46 Thus, the Federal Circuit found that Alarm.com’s reexamination request was “another, fourth iteration” of an incremental petition, that continued the abusive filing practices after the ’091 patent decision.47 The Federal Circuit then held that the Office acted arbitrarily and capriciously by ordering reexamination and denying Vivint’s petitions seeking dismissal under Section 325(d).48 Accordingly, the Federal Circuit vacated the Office’s decision finding that all the reexamined claims were unpatentable and remanded with instructions to dismiss the reexamination.49

Takeaway

The Federal Circuit’s decision in In re Vivint will likely encourage the Office to exercise its discretion against reexamination requests that merely serve as serial challenges to a patent.

From a petitioner’s perspective, previously asserted invalidity grounds that have been denied in IPR or post-grant review (PGR) proceedings should be reevaluated before being rehashed in a reexamination request. Similar to distinguishing an IPR petition from the examiner’s positions during prosecution, petitioners should distinguish the grounds for reexamination from the art or arguments previously presented in IPR or PGR petitions, by applying new art and asserting different obviousness rationales.

From a patent owner’s perspective, the grounds raised in reexamination requests should be compared to the art and arguments previously presented in other proceedings, including IPR and PGR proceedings. Patent owners should timely petition the Office to exercise its discretion under Section 325(d), especially if the request merely reasserts the same or substantially same art from a prior proceeding.

The next year should provide insight on how In re Vivint impacts the Office’s handling of the surge in requests for reexamination. But petitioners should not be surprised if the Office chooses to exercise its discretion under Section 325(d) more often during reexamination, particularly where the grounds are the same or substantially the same as an IPR or PGR, just as the PTAB has exercised its discretion more frequently in AIA post-grant proceedings.

1. IPR2019-01469, Paper 6 (P.T.A.B. Feb. 13, 2020) (precedential)(“Advanced Bionics”).

2. IPR2019-00975, Paper 15 (P.T.A.B. Oct. 16, 2019) (precedential as to §§ II.B and II.C) (“Oticon Medical”).

3. Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 11-22.

4. Oticon Medical, Paper 15 at 10-20.

5.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 8.

6.Becton, Dickinson & Co. v. B. Braun Melsungen AG, ¬IPR2017-01586, Paper 8, 17-18 (P.T.A.B. Dec. 15, 2017) (precedential as to § III.C.5, first paragraph) (“Becton, Dickinson”) (explaining that the PTAB considers the following non-exclusive factors when evaluating discretion under § 325(d): (a) the similarities and material differences between the asserted art and the prior art involved during examination; (b) the cumulative nature of the asserted art and the prior art evaluated during examination; (c) the extent to which the asserted art was evaluated during examination, including whether the prior art was the basis for rejection; (d) the extent of the overlap between the arguments made during examination and the manner in which a Petitioner relies on the prior art or a Patent Owner distinguishes the prior art; (e) whether a Petitioner has pointed out sufficiently how the Examiner erred in its evaluation the asserted prior art; and (f) the extent to which additional evidence and facts presented in the Petitioner warrant reconsideration of the prior art or arguments.)

7.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 10.

8.Id.

9. Id. at 7-8, 10.

10. Becton Dickinson, Paper 8 at 16.

11. Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 10; see also Weatherford U.S. v. Enventure Global Technology Inc., IPR2020-01661, Paper 19 (P.T.A.B. April 15, 2021).

12.See Edwards Lifesciences Corp. et al. v. Colibri Heartvalve LLC, IPR2020-01649, Paper 8 at 20-21 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 26, 2021) (declining to exercise its discretion when patent owner did not dispute petitioner’s contentions that none of the previously presented references were considered during prosecution); H-E-B, LP, v. Digital Retail Apps, Inc., IPR2020-00149, Paper 25 at 72 (P.T.A.B. May 19, 2020) (declining to exercise its discretion when patent owner did not contest petitioner’s allegations that the asserted references were not before the Examiner during prosecution).

13.Thorne Research, Inc. v. Trustees of Dartmouth College, IPR2021-00491, Paper 18 at 7-9 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 12, 2021) (declining to exercise its discretion to deny institution after finding that the combination of a reference cited during prosecution and two newly asserted references were not the same or substantially the same art previously presented to the Office).

14.Id. at 8.

15.Grimco, Inc. v. Principal Lighting Group, LLC, IPR2021-00968, Paper 13 at 19-21 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 22, 2021); but see In re Mouttet, 686 F.3d 1322, 1333 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (explaining that “where the relevant factual inquiries underlying an obviousness determination are otherwise clear, characterization by the examiner of prior art as ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ is merely a matter of presentation with no legal significance.”).

16.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 8.

17. Id. at 10.

18. See Gardner Denver v. Utex Industries, Inc., IPR2020-00333, Paper 12 at 13-14 (P.T.A.B. Aug. 5, 2020) (denying institution upon finding that newly asserted references Kalsi and Kohl are no more relevant than references that were presented during prosecution); Roku, Inc. v. Universal Elecs., Inc., IPR2019-01619, Paper 11, 16-17 (P.T.A.B. April 2, 2020) (denying institution upon finding that newly applied Zetts was cumulative to previously pre-sented Kim, even though Kim was not considered for the same limitation in reexamination); Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 13-19.

19. Dropworks, Inc. v. The University of Chicago, IPR2021-00100, Paper 9 at 13-14 (P.T.A.B. May 14, 2021).

20. Id.

21.Oticon Medical, Paper 15 at 10-20 (finding a newly raised reference—Choi—different from a previously presented reference because Choi’s implant screw grooves were located at a different portion of the screw compared to the implant screws of the previously presented art, and thereby, providing an advantage not considered by the examiner during prosecution).

22.Agrofresh Solutions Inc. v. Lytone Enterprise, Inc., IPR2021-00451, Paper 11 at 12-13 (P.T.A.B. July 27, 2021); see also London Luxury v. E & E Co., LTD., PGR2021-00083, Paper 10 at 17-22 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 15, 2021).

23.See e.g., Evapco Dry Cooling, Inc., v. SPG Dry Cooling USA, IPR2021-00687, Paper 11 at 24-25 (P.T.A.B. Sep. 24, 2021) (finding a newly asserted reference not cited during prosecution as being substantially the same as the references that were before the Examiner during prosecution).

24.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 8.

25. Id. at 10.

26. Id.

27. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., et al. v. Evolved Wireless LLC, IPR2021-00943, Paper 9 at 10-12 (P.T.A.B. Dec. 1, 2021); Carrier Fire & Security America’s Corp. v. Sentrilock, LLC, IPR2021-00664, Paper 12 at 21-23 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 16, 2021).

28. See Satco Products Inc. v. The Regents of the Univ. of California, IPR2021-00662, Paper 13 at 25 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 8, 2021); Samsung Electronics at 11-12; Carrier Fire, Paper 12 at 21-23.

29.Albany International Corp. v. Kimberly-Clark Worldwide, Inc., PGR2021-00019, PGR2021-00019, Paper 22 at 15-17 (P.T.A.B. June 22, 2021) (exercising discretion to deny institution after finding that an overlooked portion of a previously presented reference was no more pertinent in providing any teachings of allowable subject matter indicated by the examiner).

30.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 21.

31.See Weatherford, Paper 19 at 16-17.

32.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 9.

33.Evergreen Theragnostics, Inc., v. Advanced Accelerator Applications SA, PGR2021-00003, Paper 10 at 18 (P.T.A.B. Apr. 14, 2021); Albany International Corp., Paper 22 at 16.

34.Volkswagen Group of America, Inc. v. Michigan Motor Technologies, IPR2020-00452, Paper 12 at 31-33 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 9, 2020).

35.Continental Automotive Systems, Inc. v. Horizon Global Americas Inc., IPR2021-00322, Paper 7 at 19 (P.T.A.B. May 28, 2021); see also Dish Network LLC et al. v. Sound View Innovations, LLC, IPR2020-01041, Paper 13 at 21-22 (P.T.A.B. Jan. 19, 2021).

36.Advanced Bionics, Paper 6 at 8-9, fn. 9 (“Another example may include an error of law, such as misconstruing a claim term, where the construction impacts patentability of the challenged claims.”)

37.In re Vivint Inc., 14 F.4th 1342, 1350 (Fed. Cir. 2021).

38.Id. at 1346.

39. Id.

40. Id. at 1346-1347.

41. Id. at 1347-1348.

42. Id.

43.Id. at 1348.

44.Id.

45. Id. at 1350.

46. Id.

47. Id. at 1353.

48. Id.

49.Id. at 1354.

This article appeared in the 2021 PTAB Year in Review: Analysis & Trends report. To view our graphs on Data and Trends, please click here.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates