Summary

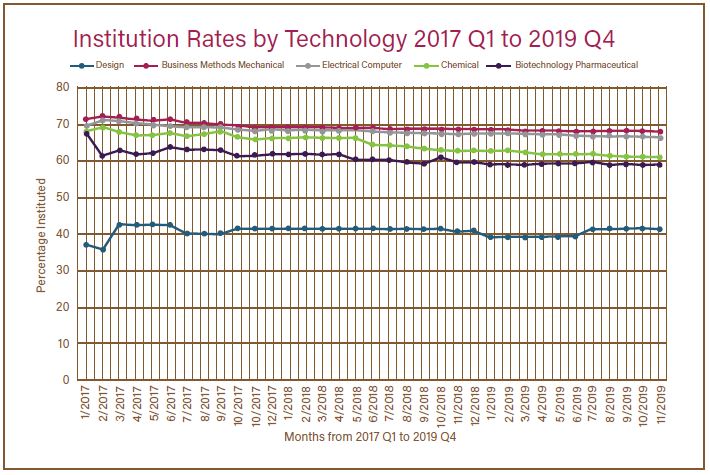

While petitioners are successful at least 60% of the time in getting the PTAB to institute trial on patents in the biotech, chemical, electrical/computer, mechanical, and business method arts, that is not the case for design patents. Since September 2016, the PTAB’s institution rate for petitions filed against design patents has remained well below 50%. To date, the institution rate is only 41%. This is based on a total of 46 institution decisions (19 grants and 27 denials).

Why are design patents escaping post-grant challenges by a significantly wider margin than their utility counterparts? The design patent institution rate reflects the fact that petitioners are failing roughly 60% of the time when they challenge design patents based on prior art. As discussed below, the legal standards governing anticipation and obviousness in the case of design patents are nuanced and the rights themselves are proving resistant to prior art challenges.

From an enforcement perspective, this is good news. Design patents are becoming an increasingly popular way to protect the ornamental appearance of products, from graphical user interfaces to automotive parts, and to stave off would-be competitors and those who are likely to copy or knock-off. The opportunity to recover the infringer’s profits also makes design patents a uniquely potent threat. Combined with their apparent resistance to challenges before the PTAB, as discussed in detail below, design patents represent a powerful tool in an enforcement arsenal.

Why does securing denial of institution at the PTAB matter for purposes of enforcement? A defendant’s failed attempt to institute post-grant proceedings lifts the specter of a stay pending review by the PTAB and often chills confidence in a defendant’s invalidity contentions. Securing denial of institution could also weigh in favor of granting a preliminary injunction. And it goes without saying that scoring an early victory before the PTAB can help promote settlement.

Here we summarize the state of play for challenges to design patents at the PTAB as of 2019 and provide some analysis regarding why design patents are showing resistance to attack.

Design patents are the only technology area with an institution rate below 50%

As shown in the graph below,1 design patents have maintained an institution rate well below 50%, which stands in stark contrast to all the other technology areas. A more granular analysis of the PTAB’s institution decision-making for design patents reveals that this is because petitioners have failed to a make a sufficient case with respect to anticipation 50% of the time and have failed to make a sufficient case with respect to obviousness 60% of the time. Grounds based on obviousness are more common than grounds based on anticipation. Grounds based on anticipation have been asserted in 22 petitions, grounds based on obviousness in 43.

These numbers are no longer anecdotal, they reveal a meaningful and sustained trend: that design patents are difficult to invalidate before the PTAB. The trend is even more significant if you take into account that the standard for institution is easier to satisfy than the burden of proof after a trial. To obtain institution, the petitioner need only demonstrate “a reasonable likelihood” of prevailing. 35 U.S.C. § 314(a). Thus, the PTAB is finding that the clear majority of petitioners are not demonstrating even a reasonable likelihood of proving unpatentability.

One reason is that the standards for design patents are specialized and nuanced

The validity challenges described above are associated with standards that are unique to design patent law. The standard for anticipation of a design patent is referred to as the “ordinary observer” test, which provides that a design claim is unpatentable if “in the eye of an ordinary observer, giving such attention as a purchaser usually gives, two designs are substantially the same, if the resemblance is such as to deceive such observer, inducing him to purchase one supposing it to be the other.”2 Petitioners have struggled to meet this standard because the PTAB often finds that differences between the prior art and the claim are noticeable, not trivial.3

The standard for obviousness of a design patent is “whether the claimed design would have been obvious to a designer of ordinary skill who designs articles of the type involved.”4 This analysis involves an inquiry with two steps: (1) “one must find a single reference . . . the design characteristics of which are basically the same as the claimed design,” often referred to as a Rosen reference after a seminal case by that name, and (2) “[o]nce this primary reference is found, other references may be used to modify it to create a design that has the same overall visual appearance as the claimed design.”5 It has been very common for petitioners to fail at the first step.6 This trend continued in 2019, with two out of the three petitions filed against design patents being denied because the petitioner failed to put forth an adequate Rosen reference, i.e., a primary reference that creates basically the same visual impression as the claimed design.7

Specifically, in Levitation Arts, Inc. v. Flyte LLC, PGR2018-00073, a post-grant proceeding involving a design claim for a levitating light bulb and base, the PTAB held: “[W] e are not persuaded that Petitioner shows sufficiently that [the asserted primary reference] is a proper Rosen reference. Petitioner presents a side-by-side comparison that reveals significant differences between [the primary reference’s] design and the claimed design.” Similarly, in Man Wah Holdings Limited v. Raffel Systems, LLC, IPR2019-00530, an IPR involving a design claim for a cup holder, the PTAB held: “Given that several elements and features that Petitioner acknowledges are part of the claimed design are altogether missing … we find unpersuasive Petitioner’s contention that the differences between the designs are merely de minimus.”

Another reason is that design patents appear to withstand prior art challenges well

While understanding the nuances of these specialized standards is one aspect of the difficulty petitioners seem to be encountering, that is not the whole story. The ability of design patents to withstand post-grant scrutiny is perhaps more accurately a reflection of the quality of original examination. In general, the PTAB seems to institute based on the strength of the art, rather than on how skillfully petitioners plead their legal arguments. If that is true for the most part, then the better explanation for the exceptional resistance of design patents to attack appears to be that the design claim is patentable and that the Patent Office has done its job thoroughly.

In sum, a significant and sustained trend has emerged that design patents are more likely to survive challenges at the PTAB at the institution stage. Not only does this trend have strategic implications for patentees, but it reflects positively on the quality of original examination.

1Source: Sterne Kessler compilation of official statistics of the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office relating to the Patent Trial and Appeal Board from January 2017 to November 2019.

2Int’l Seaway Trading Corp. v. Walgreens Corp., 589 F.3d 1233, 1240 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (quoting Gorham Mfg. Co. v. White, 14 Wall. 511, 81 U.S. 511 (1871)).

3 See, e.g., MacSports, Inc. et al v. Idea Nuova, Inc., IPR2018-01006, Paper 6 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 13, 2018); Campbell Soup Company v. Gamon Plus, Inc., IPR2017-00091, Paper 12 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 30, 2017); Graco Children’s Products Inc. v. Kolcraft Enterprises, Inc., IPR2016-00810, Paper 8 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 28, 2016); Aristocrat Technologies, Inc. v. IGT, IPR2016-00767, Paper 8 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 14, 2016); Medtronic, Inc. v. Nuvasive, Inc., IPR2014-00071, Paper 7 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 21, 2014); ATAS International, Inc. v. Centria, IPR2013-00259, Paper 11 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 24, 2013).

4Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Elec. Co., 678 F.3d 1314, 1329 (Fed. Cir. 2012) (quoting Durling v. Spectrum Furniture Co., 101 F.3d 100, 103 (Fed. Cir. 1996) (citing In re Rosen, 673 F.2d 388, 391 (C.C.P.A. 1982))).

5High Point Design, LLC v. Buyers Direct, Inc., 730 F.3d 1301, 1311 (Fed. Cir. 2013).

6See, e.g., Top of Form MacSports, Inc. et al v. Idea Nuova, Inc., IPR2018-01006, Paper 6 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 13, 2018); Skechers U.S.A., Inc. v. Nike, Inc., IPR2016-01043, Paper 8 (P.T.A.B. Nov. 16, 2016); Aristocrat Technologies, Inc. v. IGT, IPR2016-00767, Paper 8 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 14, 2016); Premier Gem Corp. et al. v. Wing Yee Gems et al., IPR2016-00434, Paper 9 (P.T.A.B. July 5, 2016); Vitro Packaging, LLC v. Saverglass, Inc., IPR2015-00947, Paper 13 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 29, 2015); Dorman Products, Inc. v. Paccar, Inc., IPR2014-00542, -00555, Paper 10 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 5, 2014); Medtronic, Inc. v. Nuvasive, Inc., IPR2014-00071, Paper 7 (P.T.A.B. Mar. 21, 2014); ATAS International, Inc. v. Centria, IPR2013-00259, Paper 11 (P.T.A.B. Sept. 24, 2013).

7Man Wah Holdings Limited v. Raffel Systems, LLC, IPR2019-00530, Paper 7 at 15, 18 (P.T.A.B. July 26, 2019) (involving a design claim for a cup holder); Levitation Arts, Inc. v. Flyte LLC, PGR2018-00073, Paper 14 at 21 (P.T.A.B. Jan. 17, 2019) (involving a design claim for a design claim for a levitating light bulb and base).

This article appeared in the 2019 PTAB Year In Review: Analysis & Trends report. To view our graphs on Data and Trends, please click here.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates