By Ryan Davis

Law360 (May 14, 2019, 10:35 AM EDT) — It has been just over five years since the U.S. Supreme Court’s Octane Fitness ruling made it easier for courts to award attorney fees in patent cases deemed “exceptional,” adding a new wrinkle to many cases. Here’s what we’ve learned since 2014 from case law interpreting the decision.

Fee Awards Are More Common, But Still Unusual

The high court stripped away a Federal Circuit test that had set a very high bar for what constitutes an exceptional patent case where the losing party must pay its opponent’s attorney fees, replacing it with a looser standard that fees are warranted when a case “stands out from others.” That has led to many more motions seeking fees and greater odds that they’ll succeed.

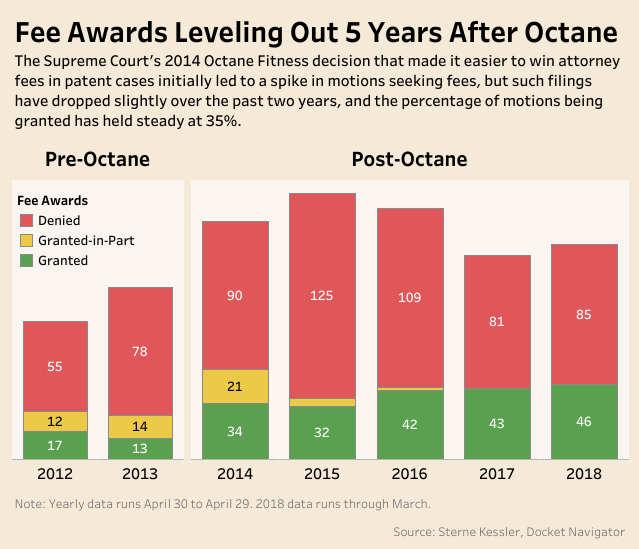

According to data compiled by Nirav Desai of Sterne Kessler Goldstein & Fox PLLC, the number of motions seeking fees in patent cases shot up in the wake of the decision but have since dropped somewhat. Fee motions have been grated at a rate of 35% over the last two years, resulting in more than 40 fee awards per year, a notable increase from the pre-Octane days.

“As far as success rates, the grant rate has been improving since Octane Fitness and has leveled off at about 35% over the last two years,” Desai said.

The landscape “has changed dramatically” since the ruling, said Douglas Cawley of McKool Smith PC. It used to be that “it wasn’t really a question of exceptional case, it was pretty well impossible case,” he said, but now, “we have a much more substantial number of district courts choosing to find cases exceptional and awarding fees.”

Judges now have discretion to decide when a case stands out from others, so “the net has been that since Octane Fitness came out there has clearly been a rise in number of exceptional case claims that have been made,” said Christopher Loh of Venable LLP.

Nevertheless, “contrary to what many people thought when Octane Fitness came out, the sky didn’t fall,” Cawley said, and exceptional case findings remain just that — an exception. Judges have applied the test reasonably for the most part, Cawley said, and “it has not led to nearly the flood of fee awards people once thought it might.”

Some Fact Patterns Drive Up the Odds of a Fee Award

What makes a case “stand out from others” is a subjective standard, but over the last five years, it has become clear that some scenarios are likely to result in fee awards.

For instance, judges have hit plaintiffs with fees for not doing an adequate presuit investigation into their infringement claims, changing legal theories multiple times without a good reason, submitting numerous arguments only to abandon them late in a case, and reasserting theories a judge has rejected.

In addition, a plaintiff’s penchant for filing numerous lawsuits and reaching for low value settlements without regard to the merits of the case has also rankled some judges and led to fee awards.

“Sometimes litigation misconduct isn’t just cabined to the case that’s before the district judge, but also pattern of misconduct across various cases,” including reaching such “nuisance” settlements, Loh said.

Decisions awarding fees generally must involve litigation misconduct or exceptionally weak theories; judges have made clear they aren’t going to order losing parties to pay fees just because they lost.

“A simple argument that it wasn’t close, without more, is not likely to be successful,” Cawley said.

Defendant Can Get Hit With Fees, Too

Fee awards are most often entered against plaintiffs for filing a weak suit, but there have also been times when losing defendants have been hit with fees as well.

Such awards usually involve cases where the defendant is found to have willfully infringed or vigorously pursued meritless defenses.

“If you’re the defendant in a patent case and you say my product clearly doesn’t infringe, and you get a determination back from the fact-finder that not only did you infringe, but you did so willful or knowingly, that’s certainly a factor that a judge would consider,” Loh said.

Nevertheless, courts have ruled that a finding of willful infringement is “relevant but it’s not determinative” for exceptional case filings, Cawley said. So willfulness is not a prerequisite for exceptional case award against a defendant and a finding of willfulness doesn’t automatically lead to a fee award.

“It’s two different inquiries,” he said.

The Risk of Fee Awards May Discourage Some Suits

Patent owners now face the possibility that if they file suit, they may not only lose but have a realistic chance of paying substantial fee awards if the case is deemed exceptional. That may be changing the calculus of when to file suit.

It’s prudent for lawyers representing patentees to advise them of that risk, Cawley said, and “I think it’s probably inevitable that if lawyers have been doing, there are a certain number of assertions that that’s made a difference in the client deciding not to bring that case.”

That may be most likely in the kind of weak suits filed to extract a quick settlement, he said, but may also be causing some patent owners to hold back on cases that may have merit, he said.

“If we’re talking about an abusive case, then that’s a good thing that that possibility has chilled the filing of that case,” he said. “If on the other hand, we’re talking about a legitimate assertion with good faith claims that still there’s room for argument about, then that may not be a good thing to chill that assertion.”

For instance, a few decisions in which judges have awarded fees based on a finding that the patent is clearly a patent-ineligible abstract idea may be giving patent owners pause, he said, since what is eligible for a patent is a contentious issue “often subject to legitimate debate.”

“In the field of software patents, without question, the risk of losing in the first instance and having the case found exceptional in the second instance is much, much greater than it was before,” he said.

Loh said he believes those types of rulings are an exception and that judges have come to realize that given the uncertainty in the law on patent eligibility “patentees shouldn’t be necessarily be penalized for allegedly weak positions based on 101.”

Octane Fitness may be discouraging some abusive or baseless suits, he said, but the fact that there are numerous decisions each year finding cases exceptional shows that “it happens and it’s still happening.”

There Are Still Some Unanswered Questions

Courts have provided some guidance on what constitutes an exceptional case in the wake of Octane, but there are still some areas of the law that need to be fleshed out.

For instance, Cawley said it’s not clear whether a fee award based on a finding that a patent was ineligible should encompass the litigation costs associated just with that issue, or the entire case. The difference could be “millions of dollars” if eligibility isn’t resolved until the end of the case, he said, and its something the Federal Circuit will likely have to rule on.

“You could argue, you didn’t have a good faith basis for this particular issue and without that, the case never should have been in first place, therefore all of it should be awarded,” he said. “On the other hand, you could also argue if that one issue was legitimately in dispute and you just happened to lose it, why should the expense of entire case be awarded.”

Loh said another issue the courts may need to address is whether litigation misconduct can give rise to an exceptional case finding by itself. Prevailing parties tend to argue both that the losing party’s position engaged in misconduct and that their overall case was weak.

While courts have suggested that misconduct alone could be sufficient, “the precise circumstances under which that occurs is not entirely clear and is court- and judge-dependent,” he said.

Since fee awards in general depend so much on the judge’s own views, it’s important for litigants to research how the judge in their case has handled the issue.

“Some of the things that will risk an exceptional case against one judge may not rise to that level against another one,” Loh said.

–Editing by Rebecca Flanagan.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates