Recent Federal Circuit decisions have held that, for a published patent application to qualify as §102(e) prior art as of its provisional application filing date, the provisional application must (1) support the relied upon disclosures in the published application and (2) provide §112, first paragraph, support for the claims in the published application. Consistent with the Federal Circuit precedent, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board has applied this §102(e) analysis to both patents and published patent applications. The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s January 2018 updates to the Manual of Patent Examining Procedure, however, seem to provide guidance for examiners that is at odds with the Federal Circuit and PTAB precedent. This article discusses the history of the Wertheim doctrine, Dynamic Drinkware and other recent Federal Circuit decisions, how §102(e) prior art has been treated at the PTAB, and as-yet unanswered questions involving the Wertheim doctrine.

The Wertheim Doctrine

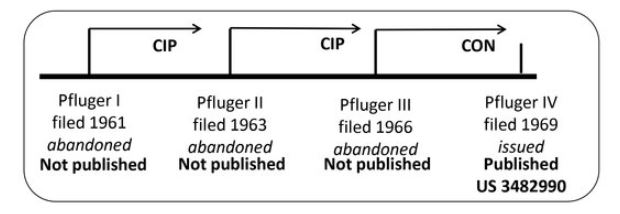

In 1981, the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals held in In re Wertheim that a patent qualifies as §102(e) prior art as of the filing date of an earlier-filed priority application only if the disclosure in the priority application provides §112, first paragraph, support for claims in the issued patent.[1] In Wertheim, the USPTO rejected Wertheim’s patent application over disclosures in a U.S. patent (“Pfluger IV”). The office relied on Pfluger IV as §102(e) prior art as of Pfluger IV’s earliest claimed priority date (“Pfluger I”). The Pfluger IV patent was filed as a continuation application from “Pfluger III,” which was a continuation-in-part application from “Pfluger II,” which was a CIP application from “Pfluger I.”[2] Each of Pfluger I, II and III were abandoned applications. At the time of Wertheim, U.S. patent applications were not published. Therefore, in the Pfluger priority chain, Pfluger IV was the only application that “published” because it issued as a patent. This is shown in the diagram below:

The CCPA’s rationale in Wertheim was based in part on the 1926 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Alexander Milburn Co. v. Davis-Bournonville.[3] In Milburn, the Supreme Court held that the effective date of an issued patent as a prior art reference is the patent’s filing date because the disclosures in the application would have been disclosed to the public on the filing date but for delays in the patent office examination procedures.[4] In Wertheim, the patent in question was a descendent of two CIP applications. The CCPA explained that, if the new matter added in the CIP application “is critical to the patentability of the claimed invention, a patent could not have issued on the earlier filed application and the theory of Patent Office delay has no application.”[5]

While the USPTO’s rejection of Wertheim’s claims relied on disclosures originally found in Pfluger I and carried forward all the way through Pfluger IV, the CCPA noted that the Pfluger IV patent itself would not have issued but for new matter added in the Pfluger III CIP application. That is, without the later added subject matter from Pfluger III, the Pfluger IV patent would not have issued and nothing would have published. The CCPA concluded that the Pfluger IV patent was not §102(e) prior art as of the Pfluger I filing date because Pfluger I did not support the claims in the Pfluger IV patent.[6]

The America Inventors Protection Act and the Wertheim Doctrine

When Wertheim was decided in 1981, U.S. patent applications did not published unless they issued as a patent. That changed in 1999, when the American Inventors Protection Act was enacted and provided for publication of patent applications filed after November 2000. At the time of its enactment, this change in law was thought by some to be the end of the Wertheim doctrine, at least as applied to published applications.[7] As one of the authors of this article wrote over 17 years ago, “it is perhaps unlikely that the PTO or the courts will apply the Wertheim rule to claims in published applications.”[8]

The Federal Circuit and the PTAB Have Applied Wertheim to Published Applications

In 2015, the Federal Circuit decided Dynamic Drinkware, an appeal from an inter partes review final written decision.[9] In the Dynamic Drinkware IPR, the petitioner relied on a U.S. patent (“Raymond”) in its grounds for unpatentability as §102(e) prior art based on the Raymond patent’s provisional application filing date.[10] The PTAB concluded that the petitioner “failed to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that Raymond is entitled to the benefit of the earlier provisional filing date.”[11] On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTAB’s decision. The Federal Circuit reiterated the CCPA’s holding in Wertheim, stating that “[a] reference patent is only entitled to claim the benefit of the filing date of its provisional application if the disclosure of the provisional application provides support for the claims in the reference patent in compliance with § 112, ¶ 1” and concluded that “Dynamic did not make that showing.”[12]

The reference in Dynamic Drinkware was an issued patent. The issue remained whether the Wertheim doctrine would be applied to the use of published applications as §102(e) prior art.

In Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, Sanofi appealed a district court decision regarding, inter alia, whether two Patent Cooperation Treaty publications qualified as §102(e) prior art.[13] Before the district court, Sanofi asserted two PCT application publications as allegedly invalidating §102(e) prior art based on their respective provisional application filing dates. Amgen argued that the references had not been established as references under §102(e) because, under Dynamic Drinkware, Sanofi had not shown that the provisional applications provided support for claims of the published PCT applications. The district court agreed with Amgen. In its affirmance of the district court’s §102(e) analysis, the Federal Circuit stated that Sanofi “did not proffer any evidence showing that the provisional applications … satisfy the written description requirement for the monoclonal antibodies claimed in the PCT applications” and that Sanofi “provided no evidence that the claims of the PCT applications were enabled by the provisional application.”[14]

Shortly after Amgen, Ariosa Diagnostics Inc. v. Illumina Inc. was before the Federal Circuit.[15] Ariosa — an appeal from an IPR final written decision — also concerned the applicability of the Wertheim doctrine to a published application (“Fan”) being relied on as a §102(e) reference. In the IPR, petitioner Ariosa argued that the holding in Dynamic Drinkware applies only to issued patents and not to published patent applications. The PTAB disagreed, stating that “[w]e cannot agree with Petitioner that the holding of Dynamic Drinkware applies only to issued patents, and not to published patent applications.”[16] In a summary affirmance, the Federal Circuit stated “the Board did not err in determining that Fan is not prior art.”[17]

Ariosa recently filed a petition for en banc rehearing of the Federal Circuit’s decision, and the court has now invited a response from Illumina.[18] As of the date of this article, the Federal Circuit’s decision on whether to grant the rehearing remains pending.

In addition to the Ariosa IPR decision, other PTAB decisions in both inter partes and ex parte matters have applied the Wertheim doctrine to published patent applications. In Forty Seven Inc. v. Stichting Sanquin Bloedvoorziening, the petitioner relied on a published PCT application as §102(e) prior art based on the PCT application’s provisional application filing date.[19] The PTAB denied IPR institution, holding that the petitioner did not “establish that the claims of [the reference PCT application publication] are supported by the disclosure of [the PCT application’s provisional application]” and therefore did not establish a reasonable likelihood of prevailing on its unpatentability grounds.[20]

The PTAB has also overturned examiner decisions for failing to apply the Wertheim analysis, which is now often referred to as the Dynamic Drinkware analysis, to a published patent application. For example, in Ex parte Lee, the applicant appealed the USPTO’s rejection of the pending claims over, inter alia, a published U.S. patent application (“Davies”).[21] During examination, the examiner relied on Davies as §102(e) prior art as of the Davies provisional application filing date. On appeal, the board explained, “the Examiner does not show that Davies’ provisional application supports the relied-upon subject matter in the rejection under 35 U.S.C. § 112, first paragraph, let alone also show that Davies’ provisional supports the claimed subject matter of Davies’ published utility application.”[22] The PTAB has applied a similar analysis in other ex parte appeal decisions.[23]

Thus, the Federal Circuit and PTAB have not limited the holding in Wertheim and Dynamic Drinkware to issued patents.

Are the New MPEP Updates Contrary to Federal Circuit and PTAB Decisions?

In January 2018, the USPTO released updates to the MPEP that included, inter alia, reference to Dynamic Drinkware. Interestingly, the update to Section 2136.03 (discussing pre-America Invents Act §102(e)) does not mention applying Dynamic Drinkware in the context of published patent applications:

[T]he reference date under pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 102(e) of a U.S. patent may be the filing date of a relied upon provisional application only if at least one of the claims in the patent is supported by the written description of the provisional application in compliance with pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. 112, first paragraph.[24]

Perhaps more information can be gleaned from the updates to MPEP Section 706.02(i) (form paragraphs), which explicitly states that “U.S. application publications and international publications do not necessarily contain patentable, or any, claims, and are thus not subject to this additional requirement, unless the subject matter being relied upon in making the rejection is only disclosed in the claims of the publication.”[25]

In view of these updates to the MPEP it seems the office’s position on whether Dynamic Drinkware applies to published patent applications may be contrary to decisions from the Federal Circuit and the PTAB. Moving forward, it will be interesting to see how these seemingly conflicting positions are resolved.

Eric K. Steffe is a director and David H. Holman, Ph.D., is an associate at Sterne Kessler Goldstein & Fox PLLC in Washington, D.C.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the firm, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

[1] In re Wertheim, 846 F.2d 527, 539 (CCPA 1981).

[2] Id., at 529.

[3] Alexander Milburn Co. v. Davis-Bournonville, 270 U.S. 390 (1926).

[4] Id., at 401 (“The delays of the patent office ought not to cut down the effect of what has been done.”)

[5] Wertheim, 846 F.2d at 536.

[6] Id., at 539.

[7] See Steffe et al., “The American Inventors Protection Act: The End of the Line for In re Wertheim?” published in Intellectual Property Today, February 2001

(available at http://www.skgf.com/themes/default/public/media/pnc/4/media.324.pdf).

[8] Id., at 5.

[9] Dynamic Drinkware, LLV v. Nat’l Graphics, Inc., 800 F.3d 1375 (Fed. Cir. 2015).

[10] See IPR2013-00131, Paper 42 (PTAB Sept. 12, 2014).

[11] Id., at 6.

[12] Dynamic Drinkware, 800 F.3d at 1381-1382.

[13] Amgen, Inc. v. Sanofi, 872 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2017).

[14] Amgen, 872 F.3d at 1380.

[15] Ariosa Diagnostics, Inc. v. Illumina, Inc., 705 Fed. App’x 1002 (Mem) (Fed. Cir. 2017).

[16] See IPR2014-01093, Paper 69, at 12 (PTAB Jan. 7, 2016).

[17] Ariosa, 705 Fed. App’x 1002.

[18] See id., Appellant’s Petition for En Banc Rehearing (Feb. 9, 2018) and Invitation of a Response from Appellee to Appellant’s Petition for Rehearing (Feb. 26, 2018).

[19] Forty Seven, Inc. v. Stichting Sanquin Bloedvoorziening, IPR2016-01529, Paper 13 (PTAB Feb. 9, 2017).

[20] Id., at 9 (citing Dynamic Drinkware); see also, Forty Seven, Inc. v. Stichting Sanquin Bloedvoorziening, IPR2016-01530, Paper 12 (PTAB Feb. 9, 2017) (same holding).

[21] Ex parte Lee, Appeal No. 2014-009364, 2017 WL 1101681 (Mar. 16, 2017).

[22] Id., at *6 (citing Dynamic Drinkware) (emphasis in original).

[23] See, e.g., Ex parte Cropper, Appeal No. 2014-001403, 2016 WL 3541264, at *4 (June 24, 2016) (holding that the requirements in Dynamic Drinkware apply to both issued patents and published patent applications); Ex parte Mann, Appeal No. 2015-003571, 2016 WL 7487271, at *3 (Dec. 21, 2016) (“both statute and case law suggest the holding in Dynamic Drinkware applies equally to any application, regardless of whether a published application or an issued patent.”)

[24] See MPEP §2136.03, January 2018 (emphasis added) (citing Dynamic Drinkware); see also, § 2154(b) (discussing post-AIA analysis, “there is no need to evaluate whether any claim of a U.S. patent document is actually entitled to priority or benefit under 35 U.S.C. 119, 120, 121, 365, or 386 when applying such a document as prior art.”)

[25] M.P.E.P., § 706.02(i), January 2018.

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates