Claim construction for a design patent is mainly focused on the drawings, which show the ornamental design that is protected by the patent. But the Federal Circuit recently identified one situation where the drawings weren’t enough to define the scope of a design patent’s claim. The scope of the claim at issue in Curver Luxembourg v. Home Expressions was defined not only by its drawings, but by the patent’s title as well.

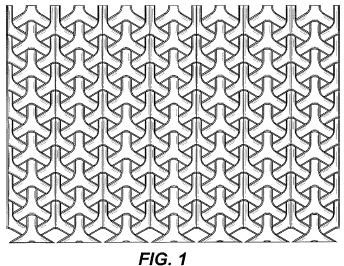

A design patent is not granted on an article itself, or on a design itself, but is granted on a design applied to an article. In essence, a design patent covers a design applied to an article. The claim of Curver’s design patent No. D677,946 is to “The ornamental design for a pattern for a chair, as shown and described.” As is typical in a design patent, the specification’s description of the design is minimal, simply describing the view from which each of the drawing figures is taken. The drawings show only a segment of material, not a chair. As required by rule, the patent’s title—PATTERN FOR A CHAIR—matches the claim. During prosecution, the title was amended from “Furniture (part of-)” on suggestion by the Examiner to overcome an objection in an Ex Parte Quayle action. According to the Examiner, the title did not designate an article to which the design is applied.

Curver sued Home Expressions alleging that baskets incorporating the patented pattern infringed the ’946 patent. Home Expressions argued that the scope of Curver’s patent is not broad enough to cover any article made from the patented pattern, but is limited to chairs, based on its title and claim language. Curver argued that its patent should be interpreted based on its drawings alone—which show only a three-dimensional material pattern—and that it thus covers the depicted material design applied to any article, not just chairs. Curver lost, first at the district court, then at the Federal Circuit.

It might seem natural that Curver’s patent is limited to a chair—after all, “chair” is in the claim. But this outcome was not certain. Traditionally, in construing the scope of a design patent, courts have focused mainly on the drawings, rather than the language, of the patent. But the Federal Circuit considered this to be a case of first impression, because it found no article evident in the drawings. Lacking this, the Court held that it was appropriate to look to the language of the patent to define its scope as a pattern for a chair. (“We hold that claim language can limit the scope of a design patent where the claim language supplies the only instance of an article of manufacture that appears nowhere in the figures.”) The Court also held that the title amendment gave rise to prosecution history estoppel such that the scope of the ’946 patent was limited by the amendment. It is unclear if the first holding relies on the second.

The Court was careful to limit its holding to cases where the claim recites an article that is not evident in the figures. Because this circumstance is rare, in most cases there should not be a similar need to import limitations from outside the drawings into the claim. But the Court’s decision highlights the need for careful attention to more than just the drawings in a design patent application. Titles and specification description should be carefully considered for their potential effect on claim scope when drafting applications as well as when making amendments to the title or specification in response to an Examiner’s objection or rejection.

As such, applicants must carefully walk a fine line between staying away from overly-narrow titles that might unnecessarily limit their claim scope, and overly-broad titles that can invite objections during prosecution. Examiners can and will object to titles that they find too broad or vague. The USPTO’s guidance says that a title and claim should recite “the name generally known and used by the public” for the article.

To help walk this line, applicants may consider balancing a comprehensive title with a carefully worded but more specific description in the specification of the nature and intended use of the design. Such statements are provided for under USPTO guidance, and may help convince an Examiner to permit the comprehensive title. This option may become more important to design practitioners seeking to maintain as filed titles in reaction to the Curver decision. Also important will be crafting such descriptions carefully and with foresight in consideration of all articles to which the design might be applied.

This article appeared in the October 2019 issue of The Goods on IP® Newsletter.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates