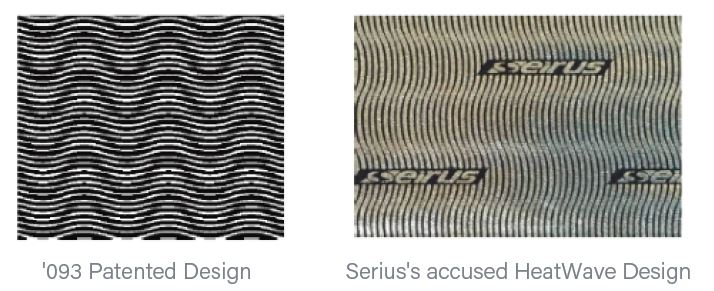

Columbia sued Seirus, claiming that Seirus’s HeatWave products infringe Columbia’s ’093 design patent for “Heat Reflective Material.” The patent claims “[t]he ornamental design of a heat reflective material, as shown and described.” The design claimed in the ’093 patent and Seirus’s accused HeatWave design are reproduced below.

The case was previously considered by the Federal Circuit, which had reversed the district court’s grant of summary judgment of infringement and remanded for a jury trial. On remand, the district court limited admissible comparison prior art to “wave patterns on fabric.” Comparison prior art is used as part of a design patent infringement analysis to determine the scope of a design patent. It “provides a frame of reference” that the trier of fact can use to determine the degree of similarity between the claimed and accused designs. The district court precluded Columbia from trying to distinguish the alleged comparison prior art references as not disclosing heat reflective material, which Columbia argued was a requirement given the claim language. The district court believed that allowing such an argument “would improperly import functional considerations into the design-patent infringement analysis.” The jury returned a verdict of non-infringement.

Columbia appealed. Among other things, Columbia argued that the district court erred in refusing to instruct the jury that comparison prior art is limited to designs that are applied to the same article of manufacture recited in the claim (here, heat reflective materials).

The Federal Circuit said the question before it—whether a prior design must involve the same article of manufacture that is recited in the claim in order to qualify as comparison prior art—was an issue of first impression. In resolving that issue of first impression, the Federal Circuit held that Columbia was correct that the scope of comparison prior art should be limited to the article of manufacture recited in the design patent claim and that the district court erred by not instructing the jury accordingly. The court found this requirement appropriate for three reasons: (i) it “best accords with comparison prior art’s purpose” to “help inform an ordinary observer’s comparison between the claimed and accused designs”; (ii) it is consistent with prior precedent from the Federal Circuit and the Supreme Court; and (iii) it harmonizes the scope of comparison prior art with the scope of anticipatory prior art. The Federal Circuit therefore vacated the non-infringement judgment and remanded the case to the district court for further proceedings.

Columbia had also challenged the district court’s failure to instruct the jury that consumer confusion as to source is irrelevant to design patent infringement and that a jury need not find a likelihood of confusion to find infringement. The Federal Circuit rejected these arguments, however, concluding that it was sufficient that the instructions (i) recited the ordinary-observer test for infringement and (ii) told the jury that it did not need to find that consumers were actually deceived or confused to find infringement.

This article appeared in the Federal Circuit IP Appeals: Summaries of Key 2023 Decision report.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates