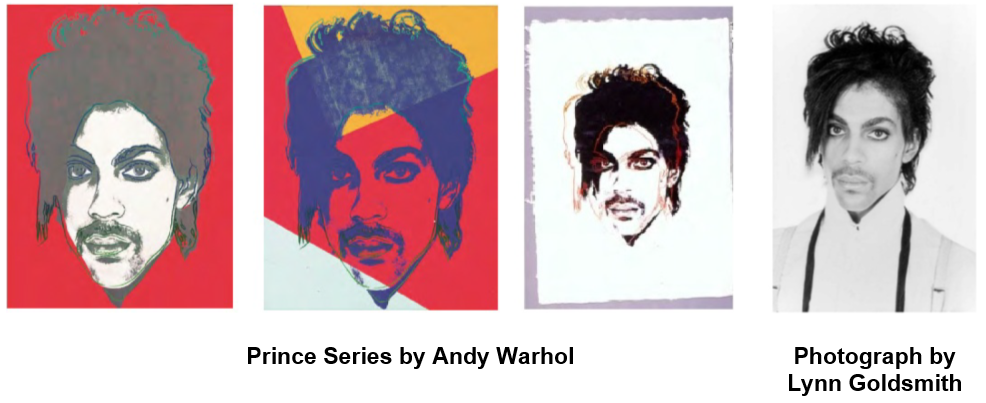

The Second Circuit recently decided whether artist Andy Warhol’s series of silkscreen prints and pencil illustrations titled “Prince Series” was a fair use of photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyrighted photograph of musical artist Prince. The images at issue appear below:

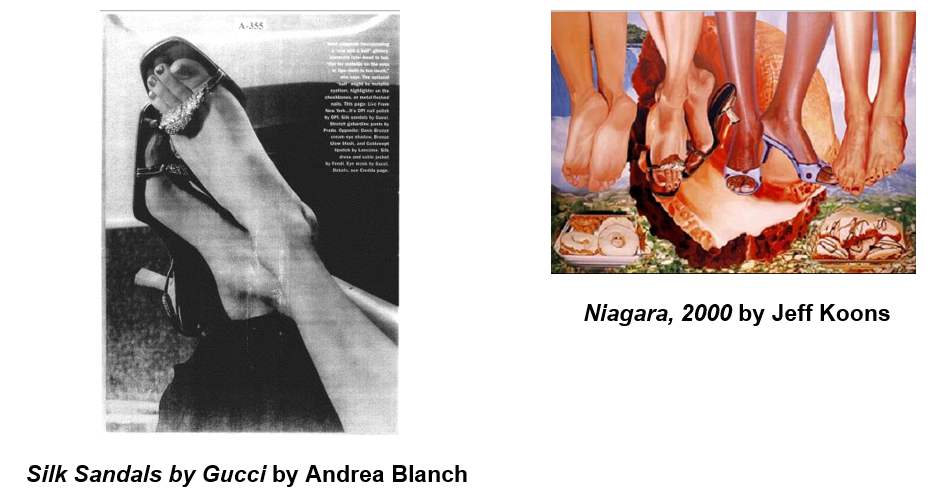

The decision is preceded by a line of cases involving the appropriation of copyrighted photographs for use in artwork, which has generally trended in favor of finding fair use. For example, in Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2006), the Second Circuit held that Koons’ painting titled Niagara, 2000 was a fair use of Andrea Blanch’s copyrighted photograph titled Silk Sandals by Gucci.

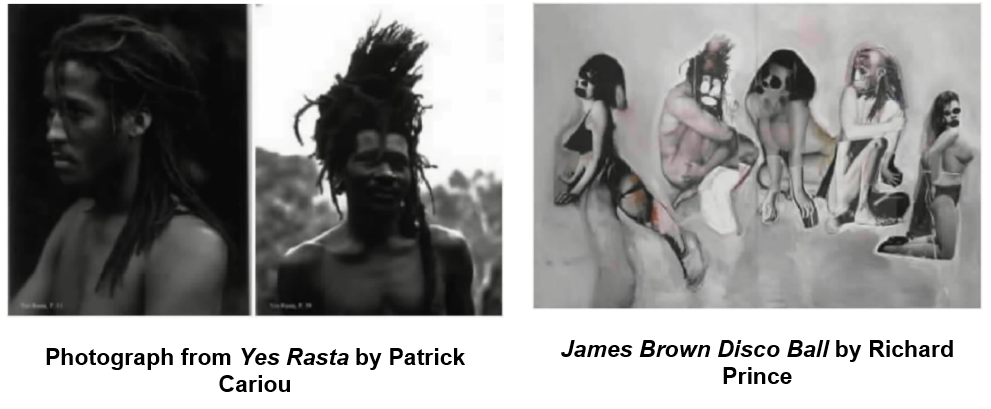

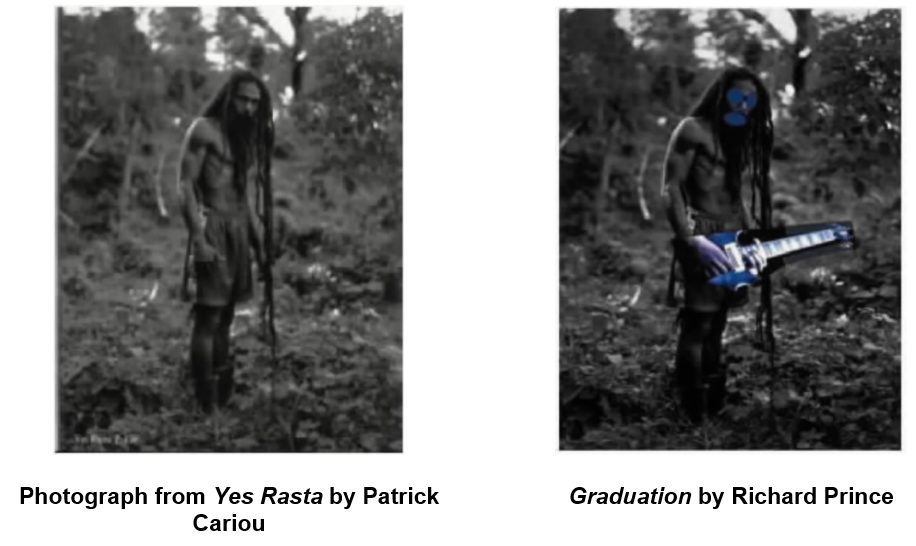

In Cariou v. Prince, 714 F.3d 694 (2d Cir. 2013), the Second Circuit concluded that twenty-five of artist Richard Prince’s paintings and collages, including a work titled James Brown Disco Ball, were a fair use of photographer Patrick Cariou’s photographs of Rastafarians in Jamaica, which appeared in Cariou’s copyrighted book titled Yes Rasta. (However, the Second Circuit declined to reach the same conclusion for five other works, including Prince’s Graduation, and remanded to the district court).

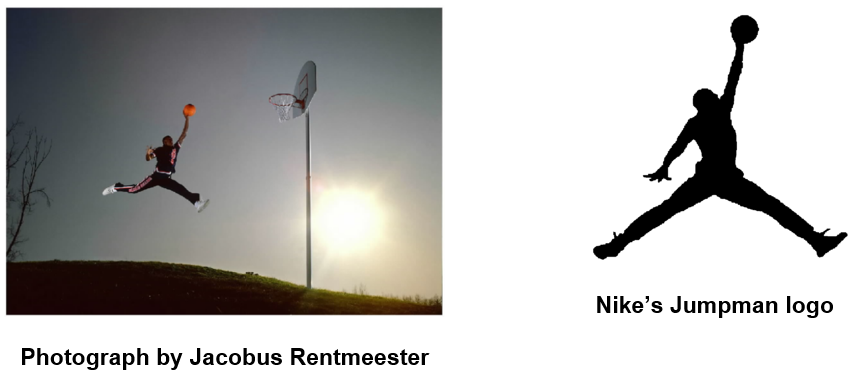

Most recently, in Rentmeester v. Nike, Inc., 883 F.3d 1111 (9th Cir. 2018), the Ninth Circuit held that Nike’s Jumpman logo was a fair use of photographer Jacobus Rentmeester’s copyrighted photograph of Michael Jordan.

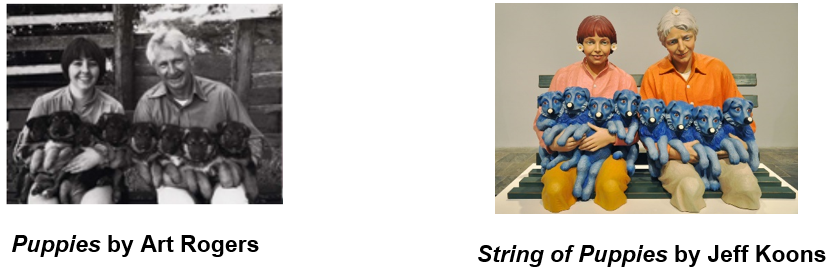

On the other hand, in Rogers v. Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992), the Second Circuit held that Jeff Koons’ sculpture titled String of Puppies was not a fair use of Art Roger’s copyrighted photograph titled Puppies:

In view of this trend, how do you think the Second Circuit ruled on Warhol’s Prince Series?

Fair Use

The Second Circuit considered the four factors of fair use enumerated in Section 107 of the Copyright Act, and found that all four weighed in favor of Goldsmith. Critical to the Second Circuit’s analysis was the first factor, which assessed whether Warhol’s use was “transformative,” or altered Goldsmith’s work with a new expression, meaning, or message. According to the Second Circuit, while Warhol changed some elements in Goldsmith’s photo to depict Prince in a characteristically “Warhol” style (e.g., removing depth and contrast, adding “loud, unnatural colors”), the Prince Series is not transformative. It simply recasts Goldsmith’s photograph with a new aesthetic, which is more akin to derivative use, not transformative use. The overarching purpose and function of the Prince Series and Goldsmith’s photograph are identical: both are portraits of the same person. Moreover, though the Prince Series can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Goldsmith’s depiction of Prince as a vulnerable, uncomfortable person into an iconic, larger-than-life figure, the Second Circuit stated that determining whether a work is transformative cannot rest merely on the stated or perceived intent of the artist.

Substantial Similarity

In considering whether the Prince Series and the copyrighted photograph are substantially similar, the Second Circuit declined to apply the “more discerning observer” test, and instead applied the “average lay observer” test. According to the Second Circuit, even though photographs, like Goldsmith’s work, capture images of reality, they nevertheless are “creative aesthetic expressions of a scene or image” and are deserving of “thick copyright protection.” Because Goldsmith’s work was undisputedly the source of the Prince Series, which was created by copying Goldsmith’s work, the Second Circuit determined that Goldsmith’s work remains recognizable within the Prince Series, and therefore, that the two are substantially similar.

Thus, the Second Circuit found that the Prince Series did infringe Goldsmith’s copyright in the earlier work.

This decision is notable because it appears to swing the pendulum away from the trend favoring fair use, and is positive news for photographers. Photographers seeking guidance on how best to protect their photographs may want to take advantage of the U.S. Copyright Office’s program that allows registering up to 750 photographs in a single application, provided that that the photos meet the eligibility requirements.

This article appeared in the March 2021 issue of MarkIt to Market®. To view our past issues, as well as other firm newsletters, please click here.

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates