By Matthew Bultman

Law360 (October 16, 2019, 5:25 PM EDT) — The number of cannabis patents and applications has ramped up as companies look to secure their place in the rapidly growing industry, staking a claim on everything from vapes to cultivation techniques. But alongside the enthusiasm, there are lingering questions about how these patents will hold up over time.

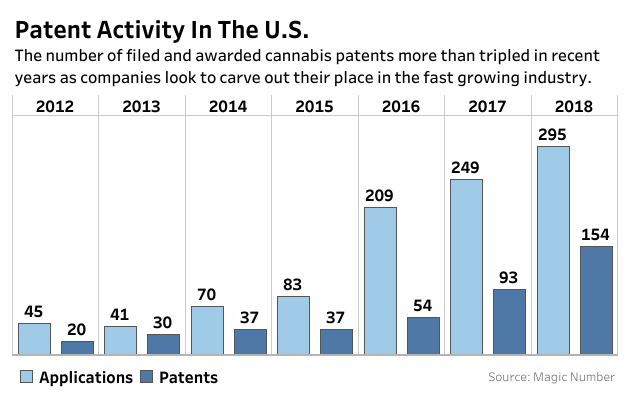

In 2017 and 2018, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office issued almost 250 cannabis patents, according to data analytics firm Magic Number. That was more than in the previous seven years combined. Last year also brought the first time a company attempted to enforce a cannabis patent in federal court.

There is a similar increase in the number of patent applications being filed. During the two previous years, the USPTO received nearly 550 cannabis-related applications, Magic Number data shows. This was on par with filing activity for the entire period from 2010 to 2016.

The surge in patent filings comes amid optimistic projections for the cannabis industry, which has seen rapid growth as more states legalize marijuana. A report from New Frontier Data, a research company that analyzes the industry, projects legal cannabis sales to reach $30 billion by 2025.

“The industry is definitely having its breakout moment,” Irell & Manella LLP attorney Josh Glucoft said. “There are a lot of reasons to think it’s going to continue to have that breakout moment and see real growth over the next few years.”

A Rush to File

Companies are filing for patents covering a range of cannabis-related inventions.

There has been a steady stream of filings from drug companies and research entities for patents covering medical treatments and pharmaceutical compositions. Others have sought patents on cannabis-infused products, including toothpastes, coffee beans and alcoholic drinks.

Filings related to vaporizers and cultivation techniques, in particular, have taken off in the past couple of years, according to JiNan Glasgow George, CEO of Magic Number and a patent attorney at NEO IP.

There are a couple of dominant filers: GW Pharmaceuticals has more than 175 patents and applications, and vaping company Lunatech has over 120. But patent activity has been largely characterized by low-volume filings from individual inventors and small to midsize companies.

Magic Number data indicates that more than 780 entities have filed for at least one patent.

“Because there’s so much happening so quickly in the cannabis industry, the way that you stake your claim in this gold rush is to file your patent application,” George said. “Everyone is trying to carve out their niche.”

Venture capital investment has been pouring into the cannabis industry, reaching a record $1.3 billion in the first half of 2019, a report from MGO ELLO Alliance found. This exceeded the amount of investment in all of 2018 and more than doubled that of 2017, the report said.

Meanwhile, cannabis companies have been on a merger spree; the number of deals doubled from 2017 to 2018. As the industry continues to consolidate, attorneys said intellectual property will be a valuable asset for smaller companies in line for a potential takeover.

A prime example is Canopy Growth Corp.’s acquisition of Colorado hemp researcher Ebbu Inc. last year in a deal worth more than $330 million. When announcing the deal, Canopy highlighted Ebbu’s “intellectual property and R&D advancements.”

“Given the potential of this market, the infusion of capital into this market and the idea that it is heavily regulated, patents are a very logical way to increase valuation and immediately put a stake in the ground for what makes your company an innovator,” Pauline Pelletier of Sterne Kessler Goldstein & Fox PLLC said.

Vancouver-based Nextleaf Solutions has placed an emphasis on intellectual property, amassing a global portfolio that includes more than 30 issued and pending patents related to cannabis extraction technology. Nextleaf has said it is the first publicly traded company to be issued a U.S. patent for the industrial-scale extraction and purification of cannabinoids.

“How do we differentiate ourselves and validate that we are unique? For us, patents was the first way to do it,” Nextleaf Chief Financial Officer Charles Ackerman said.

Yet even with the recent upswing in patent activity, attorneys say there is still room for innovation.

With respect to medical uses, specifically, David Kramer, an attorney in the hemp and cannabinoids practice groups at Vicente Sederberg LLP, said there remains a research gap between the U.S. and countries like Israel and Canada.

“As much as we’ve seen growth in patents here, we still have a ways to go as far as catching up on the research end,” Kramer said.

Federal legalization of marijuana in the U.S., which Kramer said appears to be a matter of “when, not if,” is expected to spur increased research.

“It would logically flow to me, if there is wider access to more and better cannabis there will be more innovation in the cannabis space,” he said. “And if there’s more innovation, there will likely be more patents.”

Particular Challenges

Cannabis can present some unique challenges in the patent context.

The amount of academic articles and other published information in the field remains relatively small. That means USPTO examiners, who may be relatively unfamiliar with cannabis applications, also have a smaller pool of prior art to refer to when deciding whether to award a patent.

This has led to concerns that the USPTO may be issuing some questionable patents.

Brett Schuman, co-chair of the cannabis practice at Goodwin Procter LLP, said cannabis patents can fall into a couple of broad buckets. Pharmaceutical companies, with their large research budgets and experienced IP departments, likely have some high quality, pharmaceutical-grade patents. Emerging cannabis companies fall into a second bucket. And that is where there can be some unevenness.

“I think the patent examiners really struggle with some of the cannabis patents in this [latter] bucket, and it leads to issuance of patents that probably shouldn’t be issued in the first place,” Schuman said.

The lack of prior art could make it difficult to challenge cannabis patents in the inter partes review at the Patent Trial and Appeal Board. IPR petitioners are able to argue a patent is obvious or anticipated based only on earlier patents and printed publications.

There have also been questions about the viability of enforcing cannabis patents in federal court.

Rutgers Law School professor William McNichol suggested in a recent academic article that federal courts should not entertain most cannabis patent infringement suits, citing a centuries-old rule that a court not “lend its aid to a man who founds his cause of action on an … illegal act.”

United Cannabis Corp. was the first company to test a cannabis patent in federal court, filing an infringement lawsuit last year in Colorado against a rival maker of CBD products, Pure Hemp Collective. In April, a judge rejected arguments that United Cannabis’ liquid cannabinoid formulations are not eligible for a patent under U.S. Supreme Court decisions that natural phenomena cannot be patented, allowing the lawsuit to proceed.

The legal status of cannabis has not been an issue so far in the case.

“That said, there is only this one case,” Pelletier said. “It will take more litigation to answer all of the questions that people might have about enforcing cannabis patents.”

Perhaps there are some signals outside the patent context. Schuman noted there has been litigation involving other aspects of the cannabis industry, including contract cases. Federal courts have generally treated these cases like any other.

Schuman and others expressed doubt that questions about whether the patents can be enforced have chilled the filing of infringement lawsuits.

“More likely what’s going on is people are waiting to see where the money is and who you want to sue,” Schuman said.

While litigation could be on the horizon, Glucoft said doesn’t expect to see patent wars on the level of the battles that enveloped the smartphone industry earlier this decade. One reason is simply the nature of the products.

“A phone does so much and incorporates so much, it lends itself toward this sort of crazy free-for-all,” Glucoft said. “I don’t think that [cannabis] products are as multifunctional such that it would beget the feeding frenzy that there used to be.”

–Editing by Brian Baresch and Breda Lund.

Related Professionals

Related Industries

Related Services

Receive insights from the most respected practitioners of IP law, straight to your inbox.

Subscribe for Updates